Viewed with a feminist lens: Women as props in Stanley Kubrick movies

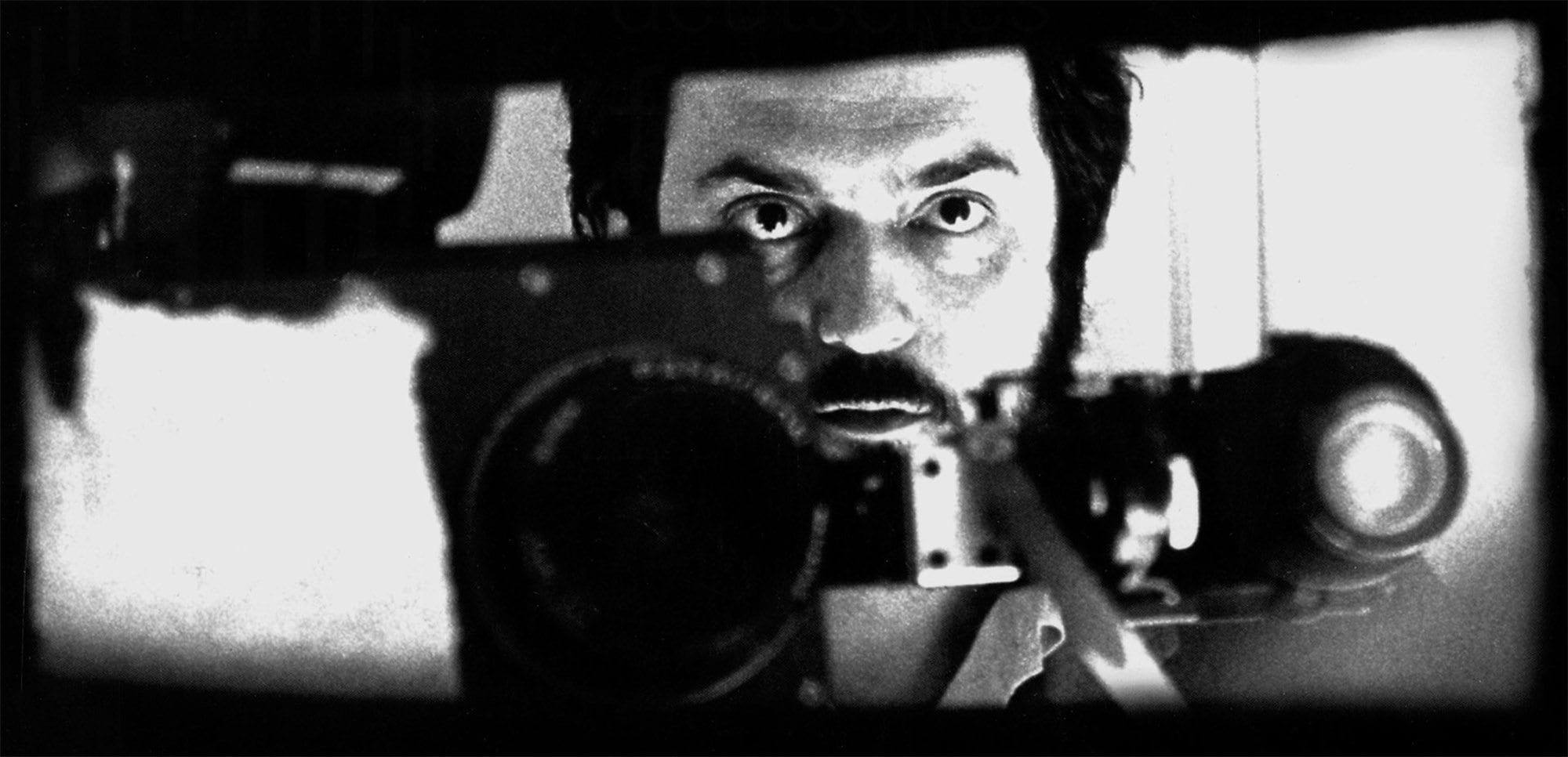

Esteemed director Stanley Kubrick (who passed away in 1999) would have turned 92 in 2020. To honor the occasion, the Twitter page posted a tribute video made up of white male filmmakers slobbering over the man’s great genius (and their own).

Martin Scorsese stares straight into the camera as though he’s delivering a cult induction video and suggests Kubrick is something “you live by”. Christopher Nolan (a director known for “fridging” the female characters in many of his films) stated that Kubrick’s movies have a “very special place” in his heart – as if we couldn’t already tell.

Meanwhile, Simon Pegg takes the opportunity to reel off more white great male directors in his honoring of Kubrick, stating, “The likes of Steven Spielberg, George Lucas, and Martin Scorsese, and Francis Ford Coppola – those guys are the movie brats that shaped the contemporary movie industry but I think all of those guys would absolutely defer to Kubrick as being a huge influence.”

White male perspective

We’re obviously huge fans of the director’s work and there’s no doubt he helped to influence an insurmountable volume of independent and Hollywood movies, but he isn’t beyond reproach. Furthermore, tributes like this that only focus on the white male perspective of his oeuvre and influence do little to counter criticisms that Kubrick’s treatment of women during production and as characters in his films was (to put it politely) a little iffy.

It’s a criticism that was brought to mainstream attention when Stephen King (who has long and openly challenged Kubrick’s treatment of his novel The Shining) called Kubrick’s depiction of Wendy Torrance (Shelley Duvall) “one of the most misogynistic characters ever put on film” in an interview with the BBC. The horror writer reasoned that the character is “basically just there to scream and be stupid and that’s not the woman that I wrote about.”

It’s a difficult criticism to argue against. For as multi-layered and truly ingenious as The Shining may be as a film, Wendy is a shrill prop of a woman – a thing to swing an axe at. The character is further worsened by Kubrick’s merciless treatment of Duvall while directing her on set.

Actor abuse

In the documentary of The Shining filmed by Kubrick’s daughter Vivian, we witness the abuses Duvall endured at the hands of the director – all in the name of enhancing Wendy’s insecurities. Such intense pressure was heaped onto Duvall that she notoriously suffered hair loss from the stress of it all and was found crying between takes.

The culmination of which is most evident in the iconic scene in which Wendy swings a baseball bat at a deranged Jack. Her hysteria is palpable and it’s also very real – it broke the world record for the most takes ever shot for a scene with spoken dialogue at 127 takes.

In the documentary, Kubrick can even be heard urging other crew members “don’t sympathize with Shelley” even though she’s stood right next to him. It’s just locker room talk, right fellas? Such jokes. Much funny.

Female objectification

Following the film’s release, Duvall opened up to critic Roger Ebert that she essentially “had to cry 12 hours a day, all day long . . . nine months straight, five or six days a week.” She also sadly lamented that for all her hard work and suffering, she wasn’t recognized for her efforts, with critics failing “even to mention it, it seemed like. The reviews were all about Kubrick like I wasn’t there.”

It’s a telling quote and it perfectly summarizes some of the criticisms of Kubrick’s work when viewed through a feminist lens. In Lolita, Eyes Wide Shut, and A Clockwork Orange, women tend to take two forms – they’re either young sexual objects or they’re elder shrews.

The lusty nymphets who strut, seduce, and are sexually and rapaciously consumed provide a framing of a woman’s power being solely beholden to her youth and beauty. The older women of these movies tend to be subsequently rendered weak and powerless and pushed into the outer frame of shots. If you happen to be a woman in a Kubrick film, you’re either there to be sexy, be a caretaker to a male protagonist, or to be a damsel in distress. Sometimes all three at the same time. You’re not a female, you’re a prop.

Misogyny and moviemaking

As Danielle R. Pearce wrote in her essay “Kubrick, Misogyny & The Human Condition”, in Lolita, “severe contrasts can be seen between mother and daughter. Kubrick clearly places Lolita in the center of frame when she is featured. This is different to her mother, whom is consistently framed off center – in the periphery. Humbert is fixated on Lolita, however Charlotte is simply an annoyance to him.”

There’s obviously an argument to be made (especially considering the satirical nature of Lolita) that Kubrick is simply reflecting societal attitudes towards women. Particularly in regards to how young and beautiful women are given prominence across all corners of society while women beyond a particular age (even a goddess like Nicole Kidman) are pushed to the outer fringes.

The problem with that reading (no matter how true it may be in regards to his intentions) is that he never made a film that truly challenged the idea of women being anything more than victims, objects, or shrews.

Toxic masculinity

In Killer’s Kiss, the heroine is relegated to the subordinate role of a frightened dancer striving to escape her dangerous boss, while in Barry Lyndon the movie explores ideas surrounding toxic masculinity, but still depicts a cheery scoundrel of a protagonist who marries a woman for her money and has his merry way with their merry maids.

In Kubrick’s further masterpieces Dr. Strangelove, 2001: A Space Odyssey, Paths of Glory, and Full Metal Jacket, women are mostly absent from the narrative. Which, in all honesty, is fine – we’re happy to enjoy a film mostly free of a female presence than one where a woman has been awkwardly shoved in for the token representation.

Kubrick’s legacy

The point is that Kubrick’s vision was such an obstinately male one that it left absolutely no space for a single complex female character or perspective. And you know what? That’s fine. Grab a spoon and eat your fill of it if that’s what you think is the marker of masterful filmmaking.

However, it leaves a bad residue upon the history of Hollywood that Kubrick is still renowned as being one of the most influential directors of all time. Especially when a modern perspective on his legacy still only offers a male white championing on the impact he continues to have on modern filmmaking.

J. Marschal

/

The word ‘whom’ used in this article should have been ‘who’.

February 2, 2020C.Sosa

/

Weak, this so weak.

April 11, 2020Jay Macinroe

/

This is really strong. Thank you.

July 17, 2020Ines

/

Very true, I found this article after realizing how misogynistic Eyes Wide Shut was. I’m sure more and more people will realize how Kubrick portrayed that same violence he practiced. Thank you for addressing this subject.

August 23, 2020Alys

/

It was hard to put a finger on what was missing in his work. Thanks for putting words to this.

November 3, 2020Space Odyssey is probably still idealized for me because of the characters, and the lack of one dimensional role

Alexander Diaz

/

A friend of mine had mentioned these issues with Kubrick films and I quickly researched and found articles such as this one addressing said issues. It’s definitely difficult to separate the film making prowess from the horrible actions against women in the films Kubrick has made. I will not see his films in the same lens again that’s for sure. Thank you for writing this up.

January 18, 2021