Why Kubrick’s ‘Lolita’ is a lot better than you might think

In 1962, Stanley Kubrick took a shot at turning Vladimir Nabokov’s formally banned masterpiece novel Lolita into a feature film. At the time, the film wasn’t a huge success, with Kubrick putting a lot this down to restrictions that were put upon him during the production of the movie. It’s also probably nearer the bottom of hardcore Kubrick fans’ lists. But why?

Lolita came after Spartacus, which despite being the film that Kubrick felt like he had the least directorial impact on (he was brought in at the last minute to replace Anthony Mann in directing the film), it was a huge box office success. Lolita then came before one of Kubrick’s greatest films, Dr. Strangelove. So historically, it’s not hard to see why it falls between the cracks.

But is history remembering Kubrick’s Lolita a bit too unfairly? Let’s take a look at some of the reasons why Lolita is the late, great auteur’s forgotten masterpiece.

The Cast

James Mason

Mason was Kubrick’s first choice to play Humbert Humbert, but due to a scheduling conflict with a play he was in, he initially turned it down. Both Laurence Olivier and David Niven then turned the role down due to “advice from their agents” before Mason withdrew from his play and took the role on.

Mason may be remembered mostly as a Shakespearean actor whose film roles never quite showed off his range as a stage actor, but Lolita is surely his best ever shot at it (with Bigger Than Life a close second). Humbert Humbert is a man who clings to his respectability and assumed social status for dear life, and in this respect no one could have carried the role better than Mason.

Peter Sellers

Sellers’s role in the film as Clare Quilty is considered by many fans of the book and the film as one of the reasons it didn’t work. In the book, Quilty is probably more of a shadow in the mind of Humbert; merely a name to go along with the madness that chases him wherever he goes.

But in Lolita, Quilty not only becomes a flesh-and-blood man for large parts of the film, but Sellers also takes on other roles that plague Humbert wherever he goes (still in the guise of Quilty). It’s maybe this playing of different roles that detracts from the impact of the film. But this critique also implies that Sellers shouldn’t play more than one role in a movie, which if you’ve seen Kubrick’s Dr Strangelove, you’ll understand is total nonsense.

Sue Lyon

A 14-year-old Lyon gives a performance well beyond her years as the slightly older than the book version of Lolita and it’s hard to see how her performance could have been improved. Jill Haworth had actually been the first choice, but she turned it down.

Nabokov himself said years later he thought French actress Catherine Demongeot should have played her, but both seem like harsh comparisons considering Lyons (at 14) managed to hold the screen with James Mason and Shelley Winters, while being directed by Kubrick.

Shelley Winters

Winters and Kubrick apparently didn’t get on too well during the making of the film, but this seemed quite common for a few of Kubrick’s leading ladies.

Conflict aside, Winters gives an amazing performance as the older woman, who clings to her dreams of being thought of as cultured and intelligent, only to be lured in by the callous Humbert who often laughs at her dreams and aspirations behind her back and even takes a relaxing bath just after she is accidentally killed outside their home.

The censors

Lolita is in many ways an erotic novel about a middle-aged man’s obsession with a 12-year-old girl. But what underlys any sense of “erotism” is the fact that the book is actually about a man’s descent into total madness. And with this, to ever make a true depiction of the book as a film, you have to include both.

Sadly, the censors of the time made it too difficult for Kubrick to express this on film and therefore the erotic element of the adaptation is slightly lost.

But this is Kubrick, so even though some of the visual elements of Humbert’s obsession with Lolita are gone, what you get instead is the relationship between Humbert and Quilty, which essentially becomes about two middle-aged psychopaths trying to kidnap the same child, which is actually a lot closer to the themes of the book than a lot of people may realize.

How could it have been better?

Well, maybe if Sellers had been given a slightly smaller role and if the censors could have treated Kubrick and the general movie-going public as adults, then that would have tightened things up – but those are only minor. Ultimately, what you have with Lolita is a darkly comic, and at times heartbreakingly sad, movie about the quiet madness that engulfs the lives of normal people set against the backdrop of post-war middle America.

Lolita is also Kubrick’s first film about madness in the individual and not simply the madness of war or money, as seen in his previous movies. It’s important to remember that the novel of Lolita isn’t a simple one and certainly doesn’t lend itself to a screenplay at first glance.

Even without these things, when you look at the 1997 remake, you can see that even without the censors being involved and without Sellers’s role, it still wasn’t easy to make and it (predictably) didn’t come close to Kubrick’s vision.

xtine

/

I just saw the 1952 version and it far surpassed my expectations. James Mason was so incredibly precise about his take on Humbert’s (deteriorating) behavior and obsession with Lolita. His scenes are riveting; you can see his decline fall to pieces (subtle) as the film moves on. He is underrated as a screen actor. I think this comes from a naturalness, a reality of presence he had; you don’t notice he’s acting. I agree that Seller’s character would have been better achieved as a menacing delirium if toned down, and the ensuing disruption gradually increasing in the viewer’s mind. Nabokov’s novel was a mind game of two men grappling for the same thing – control of an adolescent, somewhat vacuous, vixen. Which goes to say, Sue Lyon did a great job, for a 14 year old, holding her own on screen with heavy hitters of the silver screen; she was just the right amount of teenage self-absorbed dumb mixed with an adolescent’s sexually emerging awareness of power. I also think Shelly Winters hit the right shrewish tone in her portrayal of a duped, eye-wide-shut adult who also wants what she wants and doesn’t know how to navigate the territory of sexuality, her own as well as Lolita’s. Good movie worth seeing, twice.

March 28, 2020Michael Knight

/

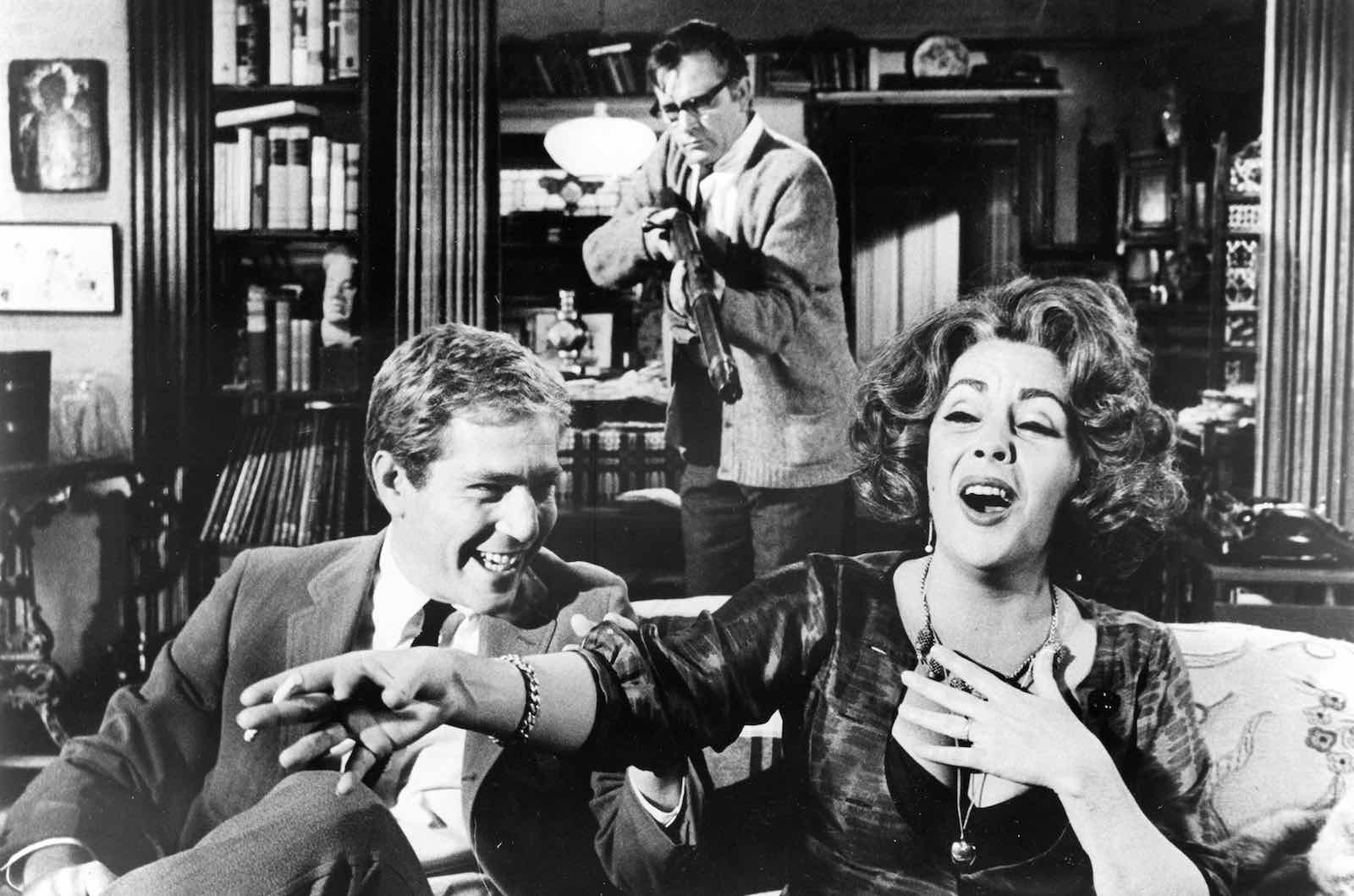

Why a picture from Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? That’s not Shelly Winters.

April 2, 2020