‘The One I Love’: Ranking the most experimental movies ever made

You would think any actor looking to break into filmmaking would avoid going for anything overly ambitious the first time round. Maybe easy sets, simple stories, a few central characters – something relatively risk free that acts as a vehicle for showing up those filmmaking talents. However, when you’re Woody Harrelson the rules do not apply. Case in point: his directorial debut Lost in London.

Not only did he decide to film the thing in a single take and base it on real-life events from his life, but it was shot live in real time – meaning any little fuck up, any mistake, and Woody’s first ever movie would forever be tarnished.

Luckily Lost in London turned out a success – a true testament to Woody’s talents both in front of and behind the camera. If you who missed it when it aired last year, Lost in London is now available to watch on Digital HD and Hulu. Check out this clip:

The energy is palpable. Instead of pushing those boundaries, Woody’s smashed them into fragments. Question is: has it got you thinking?

Perhaps seeing such an ambitious project carried out with finesse has inspired you and got you thinking that anything in possible. With such an abundance of content available to us in the modern age, it’s a prerequisite for a filmmaker to stand out and have a unique edge.

To help you get those mind maps going and creative juices flowing, here’s a ranked list of ten other experimental movies that pushed those boundaries in the same vein as Lost in London. Inspiration is everywhere!

Boyhood (2014)

Richard Linklater’s coming-of-age indie drama presents the childhood and adolescence of Mason Jr. (Ellar Coltrane) from ages six to eighteen as he grows up in Texas with divorced parents (Patricia Arquette & Ethan Hawke). While we’re not huge fans of the actual movie itself, we think Boyhood deserves a mention, as there’s no denying Linklater delivered a project that was nothing short of ambitious.

The production is what makes this movie special, carried out for twelve years so that he could truly create a film about growing up. The director wrote and developed the story on an annual basis, using the previous clips as inspiration to shape and craft the narrative and character development, allowing him to keep the same actors throughout the whole film without having to use special effects or makeup.

The One I Love (2014)

A romcom with a deliciously dark twist, The One I Love centers on a troubled couple (one half played by Mark Duplass) as they vacate to a beautiful getaway, only for the bizarre circumstances to further complicate their relationship.

Elisabeth Moss (The Handmaid’s Tale) as the other half of the couple is a complex and unusual role, while Duplass (Creep) is on top form. But what really elevates this indie flick is the fact that the dialogue was improvised. In an interview with IndieWire, Duplass explained the different type of improvisation the team used:

The script we used for this movie is highly detailed, highly plotted — it’s a 50-page outline . . . But there’s no dialogue written, so every piece of dialogue in the film is improvised . . You’re just being as organic as you can with your motivations and the trajectory of the scene, and using surprises so the person opposite you in the scene will not be lazy and rest on their heels, so it can feel, hopefully, a little bit more spontaneous than if it were rehearsed.

Tangerine (2015)

Not only was Sean Baker’s Tangerine (about a hooker who tears through Tinseltown on Christmas Eve searching for the pimp who broke her heart) hailed as a feat by the LGBTQI community, but it was also filmed solely using an iPhone 5S to accommodate the film’s tiny budget. Baker told The Verge he and his team used three different iPhones, the $8 app Filmic Pro, a Steadicam, and some adapter lenses – and that’s all, folks!

Actor James Ransone (Sinister) pointed out the key to shooting the film was having a team well-versed in traditional filmmaking. “You still need to know how editing works. Yes, you can make a beautiful-looking film on a shoestring budget, but you have to know 100 years worth of filmmaking.”

Playtime (1967)

The masterwork of French filmmaker Jacques Tati (Monsieur Hulot’s Holiday), the production costs of this daring comedy were so high that it needed to be a wide success if it wanted to cover the amount Tati had shelled out in order to make the movie financially viable. “Unfortunately the film was not a commercial success, and Tati ended up bankrupt, but the film was indeed a technical and artistic achievement,” noted Taste of Cinema.

Shot in 70mm and crafted with extremely wide shots, Playtime is notable for its huge set that Tati had built specially for the film, as well as the director’s trademark use of subtle yet complex visual comedy and innovative sound effects.

“The sets are carefully designed and crafted for the gags in which the havoc of (the main character) Monsieur Hulot is presented, and impressive order and precision. There are no close ups in the film, only perfectly composed and choreographed wide shots.”

Unsane (2018)

It’s no surprise filmmaker Steven Soderbergh has made the list, as one who ushered in a new wave of indie cinema with his feature debut Sex, Lies and Videotape and has since earned a reputation as one of the most daring, unpredictable, and exciting filmmakers around.

One of Soderbergh’s most notable feats was his recent journey into the horror genre with the thriller Unsane. Not only did he shoot the whole thing on an iPhone, but he made it in just two weeks. Despite the significant restrictions, Soderbergh nailed it – the movie was met with warm reviews following its premiere at this year’s Berlinale, showing what today’s everyday gadgets can do to push the limits of style on the big screen.

The Holy Mountain (1973)

Alejandro Jodorowsky’s surrealist epic premiered two years after El Topo and in comparison to his former film, The Holy Mountain is a far more ambitious and complete work. It’s centered on a powerful alchemist in a corrupt, greed-fueled world who leads a Christ-like character and seven materialistic figures to the Holy Mountain, where they hope to achieve enlightenment.

It’s a mind-bending journey and quite a hill to climb in terms of deciphering its many symbolic messages, but what is crystal clear is that few filmmakers have been as committed as Jodorowsky in supplying grotesque, surreal, symbolic, and hallucinatory images to hold up his masterwork.

While most people would prepare before the principal photography began by ensuring their equipment and team were in check, the auteur and his wife spent a week without sleep under the direction of a Japanese Zen master.

The central cast members similarly spent three months carrying out various spiritual exercises guided by Oscar Ichazo of the Arica Institute and the director also administered psilocybin mushrooms to the actors during the shooting of the death-rebirth scene.

The effect of the techniques are palpable when watching the film, culminating to create an enlightened experience that feels out of this world, visually, narratively, and spiritually. As the tagline says, “Nothing in your education or experience can have prepared you for this film.”

Irréversible (2002)

Auteur Gaspar Noé’s Irréversible is ambitious in its experimental style, often associated with the cinéma du corps (cinema of the body), which reportedly shares affinities with certain avant-garde productions such as an attenuated use of narrative, assaulting cinematography, provocative subject material, and a pervasive sense of social nihilism.

It’s safe to say Irréversible embodies such characteristics. Noé experimented with camera techniques, sound, and narrative, weaving the story with a dozen unbroken shots melded together. An hour of the film’s running time featured a low-frequency sound to create a state of nausea and anxiety and the narrative uses reverse chronology.

As David Sterritt noted in his novel Guiltless Pleasures: A David Sterritt Film Reader, Irréversible is not simply a story told backwards, but a complex study of the nature of time. “Its director is less interested in cause and effect than in the form of time itself.” Speaking on this topic, Noé himself stated, “The structure is all funny and the camera work is full of energy, but it’s really about losing someone you love.”

To this day Irréversible remains one of the most divisive movies ever made, but one thing most can agree on is that Noé is not afraid to work outside of the box and innovate with his stylistic techniques.

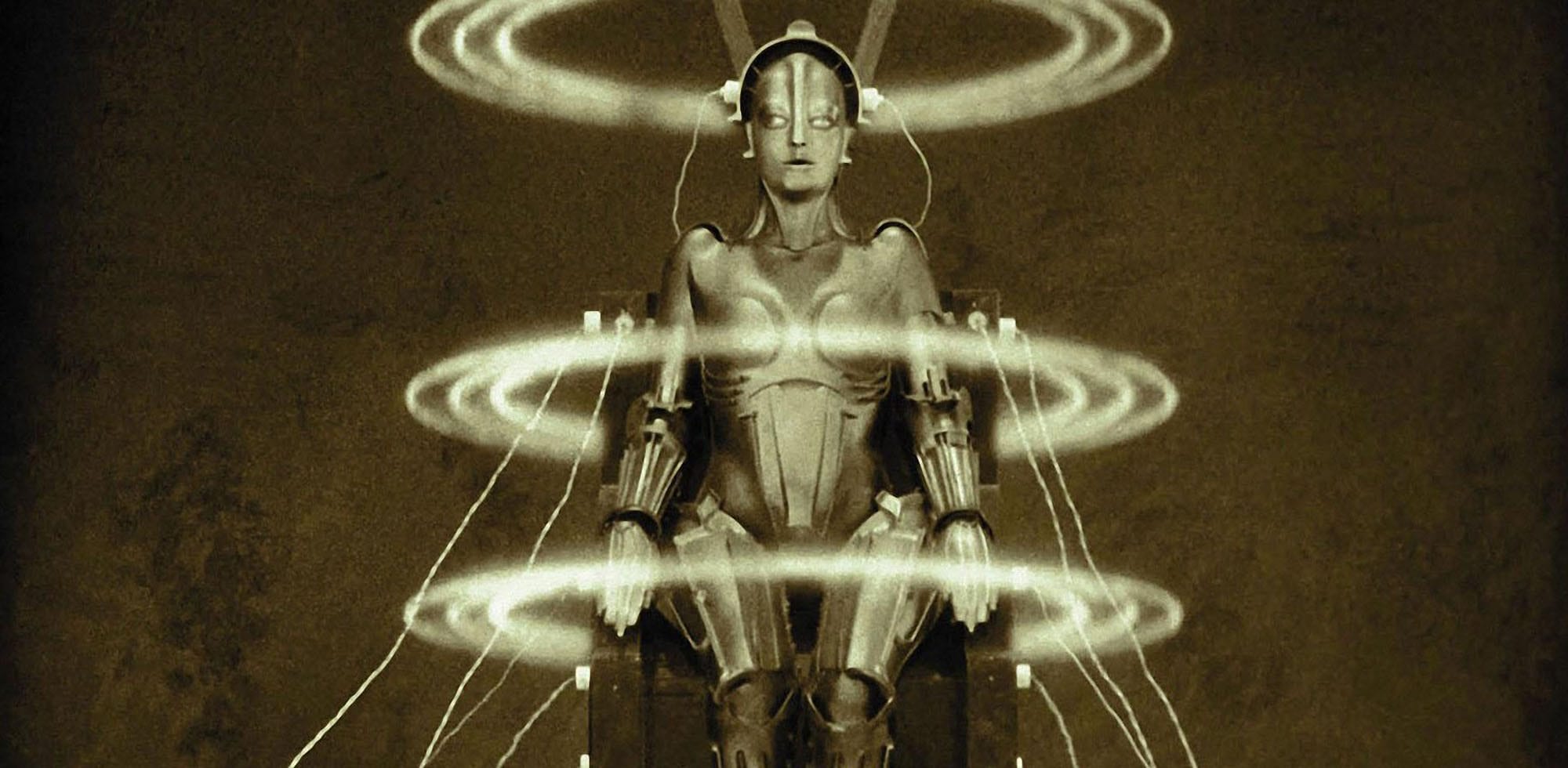

Metropolis (1927)

To say Fritz Lang’s Metropolis was ahead of its time would be an understatement – with a significant story about class warfare in a dystopian city, Metropolis is considered to be the first ever science-fiction movie.

Still inspiring visual artists, directors, fashion artists, and set designers to this day, the silent German expressionist future film remains a truly essential example of on-screen AI due to the design and biomechanics behind the False Maria robot, which went on to directly influence the design of C3PO in Star Wars.

Lang developed a range of elaborate special effects and set designs, ranging from a huge gothic cathedral to a futuristic cityscape, while filling the film with stylistic influences, from Art Deco to Gothic to functionalist modernism.

Meanwhile, cinematographers Karl Freund (Dracula) and Gunther Rittau (The Eternal Tone) relied heavily on German Expressionism techniques in order to shoot the film and composer Gottfried Huppertz (Die Nibelungen: Siegfried) drew inspiration from Richard Wagner and Richard Strauss to create a unique score put together with a large orchestra.

Not one detail of this film was not considered with meticulous attention to detail, which is why it remains one of the most important movies in science-fiction history.

2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)

Stanley Kubrick’s masterpiece might be 50 years old, but it still feels as fresh now as it did back then. A film that truly changed the face of science fiction forever, the auteur showed that the genre could and should deal with heavier themes on evolution, existence, and artificial intelligence.

The movie is a “nonverbal” experience – out of two hours and nineteen minutes of film, there are only a little less than forty minutes of dialogue – and second to character development, Kubrick used obsessive care to build his machines and achieve special effects.

As Taste of Cinema put it, “Whether it is the legendary cut between the bone and the spaceships or the interstellar voyage, Kubrick used all of the power of film to tell the story of not one single character, but of all of humankind.”