Meta-mirrors: The future of content gamification in Netflix’s ‘Bandersnatch’

Great science fiction novels create worlds so convincing, so multidimensional, so absorbing that the reader is forced to engage through the eyes of the narrative and plunge into their verisimilitude. Postmodern genre fiction has often played along the edges of reality through the use of metaconstruction and spacetime bending; finally, we reach into manipulation of the television genre itself.

Produced in 2018 and set in 1984 – including flashbacks to the early seventies – Bandersnatch manages to transcend its series, Black Mirror, to become the type of jeweled puzzle-case technodystopia right at home in a novel of the period by an author such as Philip K. Dick, whose work is directly referenced in a poster on set.

Self-reference is the name of the game here, and it creates a magical infolded density akin to the fiction of Jorge Luis Borges or Michael Ende: a choose-your-own-adventure movie adaptation of a fictional choose-your-own-adventure video game based on a fictional choose-your-own-adventure novel called Bandersnatch by fictional author Jerome F. Davies, fictionally famous for murdering his fictional wife after fictionally writing it.

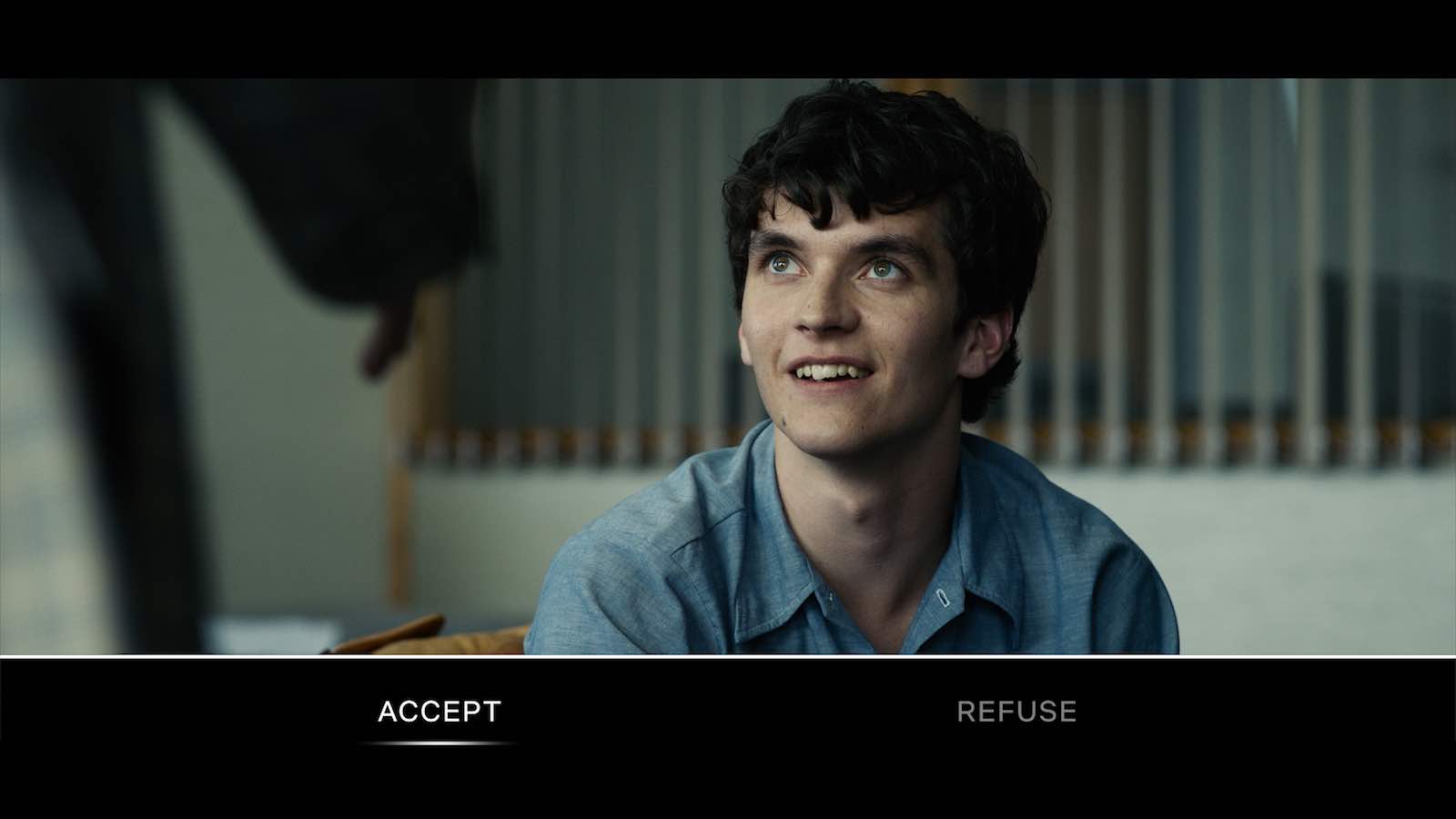

The recursion would disappoint if it ended there. After you, the viewer/player, make a few decisions for aptly named protagonist Stefan Butler (a riveting Fionn Whitehead), the young game programmer cottons on to the jig, expressing his quite appropriate paranoia at the situation. Stefan’s feeling of lack of control becomes a major theme of Black Mirror: Bandersnatch as we callously interfere in his life.

Mirrors, the ultimate symbol of reality-bending and namesake of the series, feature prominently in the story – after all, bandersnatches come from Lewis Carroll’s world Through the Looking Glass. Time travel, conspiracies, evil psychological experiments, LSD, and the Thompson Twins fit like a glove over the scenario.

At one point, fellow programmer Colin Ritman (played with iron conviction by Will Poulter), classic magician archetype of this tale who sees through their illusion of choice, outlines the multiverse theory to Stefan: actions from one timeline can affect others, even though you may not see the results in yours.

That plays out in the show’s branching decision tree, in which paths converge and combine to create Stefan’s destiny and flashbacks give us varied versions of the past.

The player – certainly Bandersnatch is no movie, but a game – is thrown into this situation with only a few minutes of background story. And as in a video game, every player’s experience is strictly unique; while we may speak of the same maze of mirrors, our paths through it necessarily must diverge.

All the metalevels inside Bandersnatch confront us with the unspoken (at least until the credits) next paradigm higher: the creators of Bandersnatch are the ones really pulling the strings behind the scenes. Audience-players are suffused with the unfamiliar experience while “watching” of not knowing whether our decisions matter or not. Frosted Flakes or Sugar Puffs? “Program and control”, indeed.

Through it all, Bandersnatch manages never to lose its plot, despite giving us the freedom to do so. You’re trying to shepherd Stefan in the creation of his computer game, and we get quite a direct score at the end. It’s here the horror elements combine with the game to produce endings of varying results but a quite consistently dismal tone. (No one ever said game design was easy.)

Choose-your-own-adventure’s heyday in the 80s saw an explosion of gamified literary storytelling, but a number of obstacles stood in the way of its long-promised transfer to the world of video.

Technology has certainly solved all those issues by now, and it was only a matter of time until a team tackled the complexity of the genre’s good old-fashioned narrative design – and longer shooting schedule to account for the story’s many branchings-off.

To have succeeded at this challenge technically would be sufficient, but writer-showrunner Charlie Brooker and director David Slade managed to spearhead an aesthetic marvel too.

“Well that is a first. And so your rating is?”

“My rating is five stars out of five – magnificent.”