True Crime: Learn about the people who froze to death on Starlight Tours

Canada has built up quite the reputation over the years. Our neighbor to the north is generally known as the nicest, most laid back country. The chillest (and sometimes chilliest) place in our continent. Canada is where we threaten to move to when things don’t go our way in the United States.

And yet, Canada is far from perfect. While the Canadian dark side is far less cartoonish than what South Park would have you believe, it does exist. There’s crime in Canada. True crime.

Have you heard of the “starlight tours”?

Starwhat now?

Let’s start by bringing up a place most Americans (except for those obsessed with true crime) probably haven’t heard of. Welcome to Saskatoon, the biggest city in the Canadian province of Saskatchewan. Saskatoon gets its name from the Saskatoon berry, exclusive to its region, and has such colorful alternate names as “Paris of the Prairies” & “Bridge City”.

Saskatoon is also home to the Saskatoon Police Service, the infamous police force responsible for the starlight tours. Not exactly the kind of stuff they advertise on tourist pamphlets, but that’s what true crime journalism is for, isn’t it?

The term “starlight tours” refers to the practice of taking Indigenous Canadians (yes, it’s that specific) and driving them to the edge of the city in the dead of Winter, where they would be abandoned. For extra kicks, police officers would take their victims’ clothing, leaving them not only stranded, but also unprotected from the sub-zero temperatures.

Freezing deaths

While it’s unclear how many victims have succumbed to the practice of starlight tours, there are three officially documented deaths associated with them.

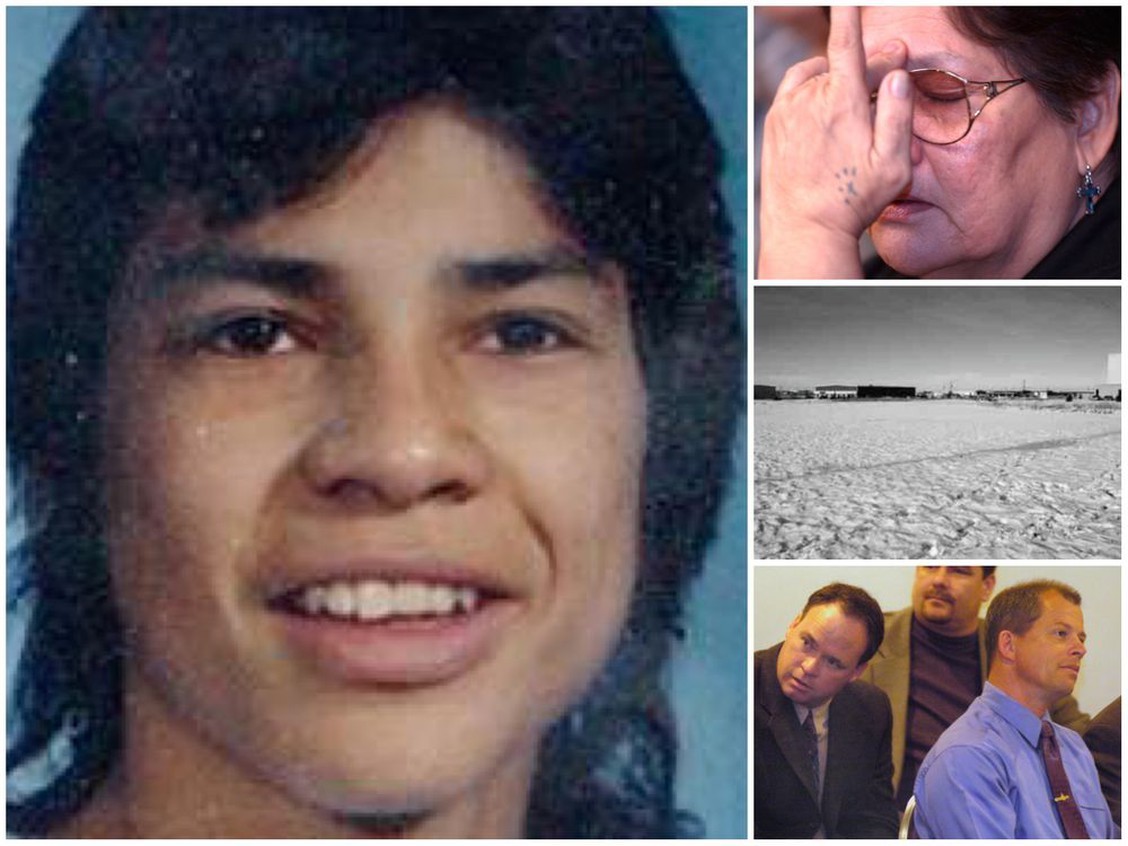

Rodney Naistus & Lawrence Wegner died in 2000, their bodies discovered on the outskirts of Saskatoon. An investigation into their demise revealed hypothermia as the cause of death and brought about a set of recommendations related to police policies & indigenous-police relations.

The third victim was Neil Stonechild, a seventeen-year-old whose death wasn’t fully investigated until 2003 – even though his body was found in 1990 in a field outside Saskatoon. The inquiry into Stonechild’s death resulted in the firing of the two police officers who were suspected to have abused him. That said, the investigation was unable to conclude what the circumstances surrounding the teenager’s death were.

Close call

As is the case in many true crime sagas, some victims are luckier than others. In January 2000, Darrell Night actually survived a starlight tour, managing to reach a nearby power station and call a taxi after being abandoned outside Saskatoon. The two police officers responsible for Night’s near-death experience would later claim they’d simply given Night a ride home and dropped him off at his own request.

Those officers were Dan Hatchen & Ken Munson of the Saskatoon Police Service. Despite their attempts at painting themselves as an alternative Canadian rideshare service, Hatchet & Munson were eventually convicted of unlawful confinement in September 2001 and sentenced to eight months in prison. Darrell Night’s ordeal would later be immortalized in Tasha Hubbard’s documentary Two Words Colliding.

For years, the Saskatoon Police Service insisted all these were isolated incidents that didn’t reflect an actual issue within their police force. However, in 2003, police chief Russell Sabo revealed the existence of a 1976 disciplinary report that implied starlight tours had possibly been a problem for almost thirty years.

PR mess

Apparently, someone in the Saskatoon Police Service didn’t feel the institution had been embarrassed enough by the freezing deaths outside Saskatoon. In a bizarre turn of events, between 2012 & 2016, the “Starlight Tours” section of the Saskatoon Police Service’s Wikipedia page was deleted multiple times.

Anyone who’s ever battled Wikipedia moderators knows self-editing your page is a losing proposition. An internal investigation concluded two of the edits were made from a computer within the police service (they couldn’t even hire a hacker?) but a spokesperson for the force denied the Wikipedia edits were approved by the Saskatoon Police Service. The rogue anti-Wiki crusader was never identified.

The idea of an incognito Saskatoon police officer editing a Wikipedia page over & over again for four years is the kind of ridiculous coda many true crime fans would treasure. Of course, the silly attempt is now also recorded on the Saskatoon Police Service Wikipedia page.

—

Ever since the Neil Stonechild investigation, the Saskatoon Police Services claims they continue to move forward on positive work regarding relations between the police & Indigenous Canadians. Hopefully, that means we’ll never have to hear about new starlight tours again.