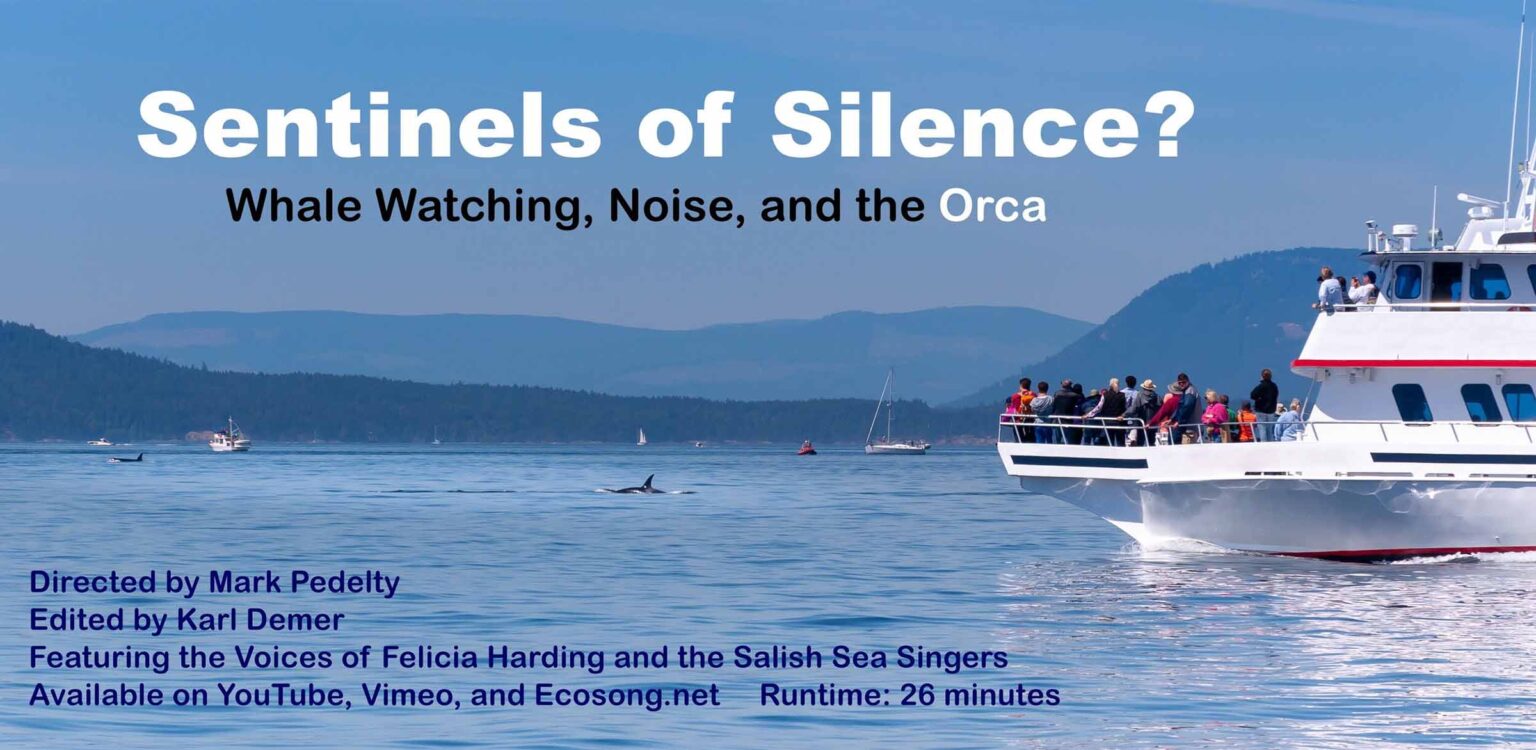

‘Sentinels of Silence’ exposes the dark side of whale watching

Documentaries have been a long-standing way for filmmakers to spread a crucial message to the world. Using storytelling combined with real-world truths, documentaries allow people to learn about important issues, while also giving their opinions on the subject matter.

Director Mark Pedelty is no stranger to the power of documentaries, as he directed his first one, A Neighborhood of Raingardens, back in 2008. Now, he’s taking on the dangers of the whale watching industry with Sentinels of Silence.

We spoke with Pedelty about his experience with Sentinels of Silence and the projects he’s working on with his company Ecosong.net.

Talk us through your filmmaking journey. What did you do before becoming a filmmaker?

As a prof, I had been writing books and journal articles for about 15 years before turning to producing and directing films.

And, the segue was making music. Through doing musical work with environmental partners, I was asked to make a documentary for our awesome partners at Metro Blooms, and that led to making music videos bringing together a diverse range of talented people to get word out and increase organizational esprit-de-corps with community partners.

In fact, through doing that in the Salish Sea, we learned about the story at the heart of Sentinels of Silence?, our current film about a whale watching controversy.

What five documentaries do you think everyone needs to see in their lifetime?

I am going to get very conventional and Media Studies-ish here and recommend those that made a big difference in public awareness and policy, An Inconvenient Truth, and one that I found very moving and enlightening: Musicwood.

The Global Assembly Line was the most eye opening and prescient film I ever watched, telling us over a decade before NAFTA what the world would look like in 2020. Sadly, it was completely accurate in terms of the inequitable impact of corporate control of the planet’s people and resources. And, that brings us to The Corporation. Years of Living Dangerously, which is also important.

Who are your current influences?

All of the above, Naomi Klein, and all of the community partners that we work with at Ecosong.Net.

Are there any particular documentaries that inspired you to create your own?

Speaking of Naomi Klein, I think No Logo helped me to see that something could be investigative, accessible, and moving, without sacrificing depth. Oddly, I was less influenced by film than print in that regard. And, per the music video emphasis of Ecosong.Net, I think that the music video is the most under-appreciated art form of our time (our time being since the invention of MTV) ☺

What was the first film you worked on, and what was your experience with it?

A Neighborhood of Raingardens. Thanks to all involved, it turned out really well. Wish I would have had the experience and savvy to distribute it, send to festivals, etc., but it seemed to really hit the mark with its intended audience among raingarden advocates and community partners.

Do you have any experience with mentors? Would you recommend them to up and coming filmmakers?

Shout out to a Berkeley prof, Jack Potter, who pushed filmmaking before I was ready to take in that lesson. And, I attended lectures and films by Timothy Asch at USC in the one semester I was able to afford there as a starting undergrad. That is a once-in-a-lifetime experience, and probably had more impact than I realized at the time.

What inspired you to create Ecosong?

People. Everyone has something to contribute to media making, and co-production does magical things in a community.

How did you find people to join together with you to work on Ecosong projects?

The principle of free association. If I learn someone loves to do body art, and I see their work, I ask them if they want to get involved. Substitute music, cooking, gardening, etc. for “body art” and you can see what I mean. Just as often now, people see what we do and ask us how they can get involved.

That is how I started working with the best songwriter and guitarist I’ve ever known: Tim Gustafson. It’s the people and their unique talents, like Bob Poch (drummer), Jayanthi Kyle (singer, composer), Becky Rice (organizer), Dana Lyons (rock star), and so many many more, that make it all work.

Walk us through your creative process.

This is my best explanation of my creative process, albeit a bit idealized there.

What inspired you to become involved in environmental activism?

The problem with age is that the explanations get longer than the answers merit. Ted Baxter’s “It all started in a 500 watt radio station in…” So, I will just mention the first. As a kid I only felt truly happy when I was in the lake or running through the few stands of trees you could find in Northern Iowa.

And, coming from a cattle family I learned early that if you want to change or build something, talking about it or just pointing fingers is never enough. It takes learning, which takes work, organization, and the kind of love for something that sustains that effort. For me, ecological engagement puts it all together.

How did you first hear about the controversies with whale watching activities?

First, I saw some egregious behavior by whale watching boats, including one time while I was kayaking alone on the North Coast of Orcas Island. Second, I read the bioacoustics literature and began doing some work with sound. Third, while making a music video about sound in the marine environment, I learned about the policy controversy explored in the film.

What inspired you to create Sentinels of Silence?

Each of those things: direct observation, science, and a clear recognition that an important perspective had been repressed by the power of money, politics, and law, and in a way that I have come to realize is harmful to the Southern Resident Killer Whales.

What was your experience working on the documentary?

During COVID, it was difficult, but gratifying and edifying. I enjoyed safely working with all informants, including, and especially, Jeff Friedman, President of the Pacific Whale Watch Association. He represents the Association well and is a really cool guy.

Do you personally feel the whale watching industry is detrimental to the health of orcas?

Sadly, yes, especially in the way that they have used their money and influence to thwart moves to create sanctuaries in the most important feeding grounds in the Salish Sea. This is the home for this amazing, culturally rich species. The Salish elders tell us that the orca are our relatives. We are treating our family so poorly.

Do you plan on exploring the whale watching industry any further in a future project?

Doubtful, because I went broke doing it this time.

While working as a filmmaker, you’re also a professor. What lessons have you learned while filmmaking do you hope to pass on to your students?

Care. I don’t care what kind of politics, media, or civic action one pursues, but if you truly care you will do some good.

People make a major distinction between Left and Right, but we should also think about that important division between those that care and those that don’t, those that take and those that give, those that are open to ideas and those that seem to be fine with the set of instructions handed them at birth. I hope that students care and remain curious.

What’s your favorite film of all time?

There is an ongoing joke in my family that it is Young Guns Two. And, to be honest, I loved that movie as a kid. What to do in the face of overwhelming odds is always a good theme, but I fear that the gender, racial, and colonial ethics of that film might not hold up! I am not brave enough to rewatch it and find out.

Seriously, though, so many films that I have loved over the past almost six decades, but I will honor your question and narrow it to one. No film has moved me more than Amores Perros, from the triptych storytelling that all comes together in such a human way to the amazing soundtrack. I still listen to that soundtrack a lot.

And, the last movie I saw, Peanut Butter Falcon, had me answering “Party!?” to about every question that I’ve been asked. I am in awe of that kind of cinematic storytelling.

Where do you see yourself in five years?

Reminds me of John Meynard Keynes when asked for a long term economic forecast: “In the long run, we’ll all be dead.” Hopefully I make it past 62, but one of the only things that gets me through some of these very difficult, have-to-scratch-that-itch, media projects, is a promise to myself and my amazing life partner, Karen Miksch, that I will return to just writing journal articles and books.

Those are hard enough without adding media production. Having said that, the latest Ecosong.Net projects, Song Gardens and Together Alone are really hitting the mark and seem to be fulfilling a purpose for those of us that are involved, and hopefully our wider communities.

What’s next on the docket for you?

Working with Taylor Leapaldt and Karl Demer on the Together Alone project has been a blast, and I think it might have a future. I really hope that the “make your own music, media, and place” ethos of the project sustains it and helps it achieve the goals of musical stewardship and placemaking.

I think we need that. It will officially launch soon via a TedX promo, but as you can see at the website, there are already a bunch of really amazing video performances there.

Do you have any recommendations on how we as individuals can help work towards environmental stability?

In addition to the most important actions—vote, organize, participate in policy decision making, and also the retail level connections that help us to actualize our environmental ethics and rhetoric—I would invite everyone to share their musical and cinematic statement with us through Together Alone.

If any director could direct the story of your life, what would you choose and why?

I’ll stay on theme: Tyler Nilson and Michael Schwartz seem to really pull humanity out of all of their characters, without falling into cliché.