‘The Misandrists’: Exploring Bruce LaBruce’s provocative punk vision

With an eclectic career stacked full of acerbic and audacious films, Bruce LaBruce is one of the boldest independent filmmakers of all time. Unafraid to push boundaries (and buttons) and to provoke and scandalize, the Toronto based filmmaker has a rich portfolio of features, shorts, artwork, and writing offering sharp explorations of LGBTQI identity, sexuality, and gender politics.

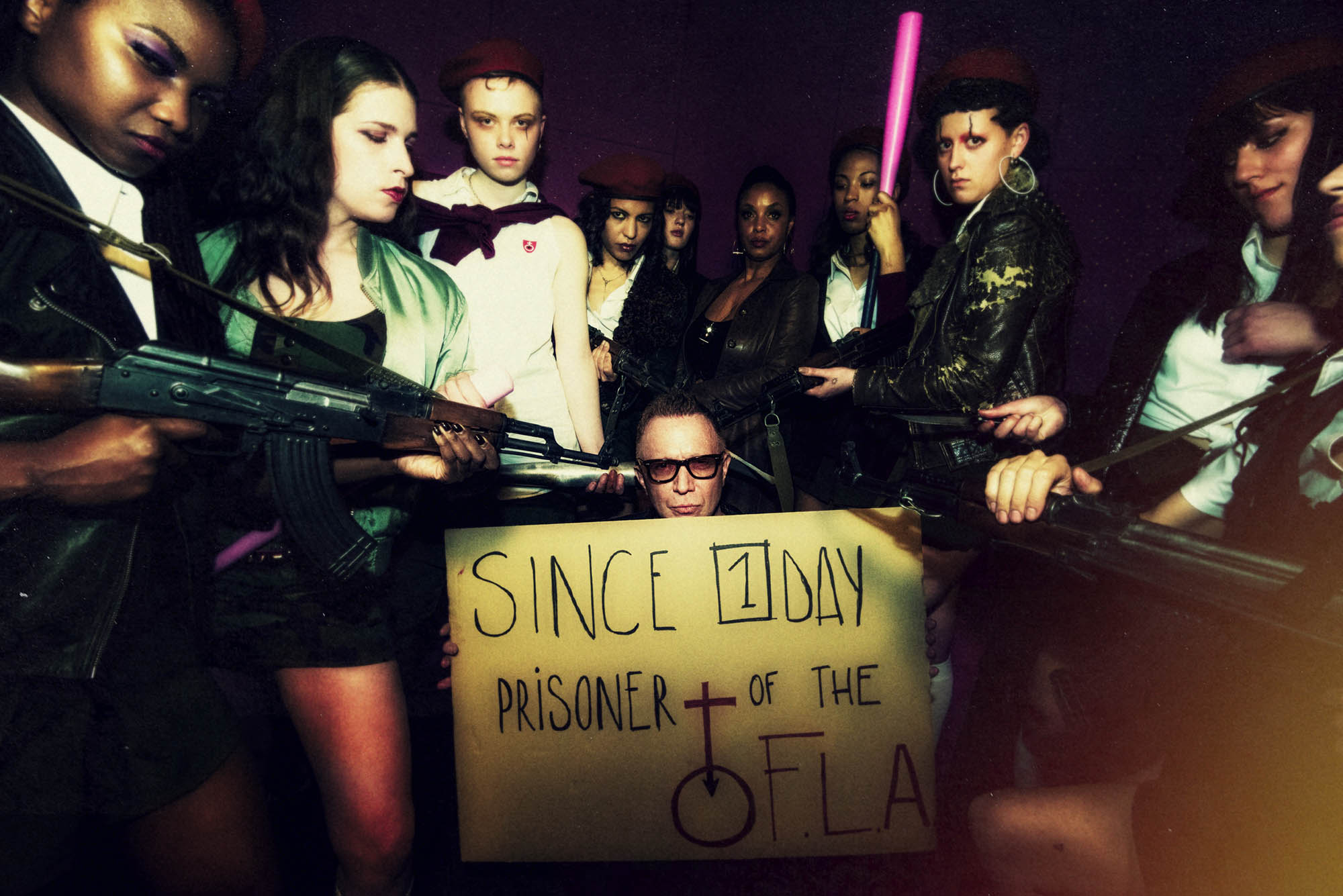

LaBruce’s work has always challenged the status quo in startling and wonderfully obscene ways and his new film The Misandrists is no different. Centered around a radical feminist terrorist group and an injured male leftist who is being secretly hidden in the basement of their remote stronghold, The Misandrists presents a sharp and salacious social commentary about radical leftist ideologies.

Film Daily caught up with the punk provocateur to talk feminism, pornography, political correctness, and why so many modern movies make him want to puke.

Film Daily: The Misandrists is full of classic erotic imagery (Nuns! Schoolgirls! Educational porn watching!) made wonderfully sapphic by the lack of men around to titillate with it. Was this a deliberate repurposing of traditional porn imagery and if so why?

Bruce LaBruce: The Misandrists is an homage to a variety of Exploitation films, from Nunsploitation to Sexploitation (particularly the erotic softcore films of the seventies, many of which had lesbian undertones), to B-movie horror (there’s a bit of Flesh for Frankenstein in there!), to the classical Hollywood exploitation style of such directors as Don Siegel and Robert Aldrich.

The film references their movies The Beguiled and The Dirty Dozen respectively, and also Ida Lupino’s The Trouble with Angels! Oh, and also the Reform School Girl films, specifically Bambule, which was a movie written by Red Army Faction member Ulrike Meinhof, whose writings I reference quite strongly in The Misandrists.

One of my trademarks as a filmmaker is to repurpose or “queer” certain classical movies or genres to politicize them, to make them radically feminist and / or radically gay, or sometimes to draw out the latent subversive subtexts of the originals, or to critique them for being sexist or homophobic, or both!

I do the same with porn, harking back specifically to seventies porn, which was often made by filmmakers or artists in the spirit of sexual liberation and to challenge the constraints of the dominant order in terms of sexual representation. The Misandrists takes pro-female porn a step further, trying to eliminate men from the equation altogether.

The film is also very much about spectatorship – drawing attention to how people, specifically men, actually watch pornography, and subverting it, partly by having the women in the film make the porn themselves and control the gaze without any male intervention and at the end showing it to pleasure women (and a few open-minded men).

In punk and queer circles there seems to be an ongoing charged debate concerning extreme shows of political correctness and political incorrectness. Apparently no-one can have fun anymore! As a filmmaker who likes to play with political incorrectness, how do you feel about the constant back and forth regarding what is and isn’t appropriate?

I’m really dismayed by some of the programmers at major LGBTQI festivals – including Toronto, San Francisco, and Los Angeles – who decided not to show The Misandrists for politically correct reasons. I have a history with all of those festivals, and it’s obviously a very zeitgeist-y, relevant movie for the times, having played at International Film Festivals from Berlin to Istanbul to Kolkata to Karlovy Vary to Helsinki and beyond, so rejecting it on those grounds is annoying.

Certain audience members may find the movie offensive and they are more than welcome to walk out or write a blog about it or send me death threats or whatever (well, maybe not death threats), but to enact prior censorship is really bad form.

Whether a film is “appropriate” or not, or if it makes people “uncomfortable” should never be a criterion for good or funny cinema. And how many films pass the Bechdel test by a thousand per cent? The most interesting films for me are those that challenge the very notion of what is taboo or not, or that explore where the limits of representation are. If conventions aren’t consistently challenged or questioned, then there’s no way for art or culture or society to move forward. A sense of humour also definitely comes in handy.

The Misandrists has a great transgender plotline that tackles the current political climate where certain feminists don’t believe transgender women are “real” women. Why do you think it’s still such a struggle for some people to accept the transgender community?

When I was a queer punk in the eighties, I used to hang out with lesbian separatists, which isn’t easy by definition, but I could totally relate at that time to their desire to have women-only spaces or environments. It’s part of the militancy of any nascent liberation movement, a strong statement against historical exploitation and violence and subjugation.

(I could also understand why certain gay men craved a completely male environment, considering the history of oppression of gay men and violence waged against them, even though I was personally more into inclusion and solidarity between fags and dykes and transgender people.)

But I also have known personally many M-F (male to female) transgender people over the years that feel in their hearts and minds and bodies that they are women (trans men too, of course, in the other direction). So the movie is politically sympathetic, you might say, to the essentialist ideals of Big Mother, but it also appreciates women-only communities that accept transgender people as women, something that might come from really spending time with and trusting and getting to know one particular transgender person in your life.

As a filmmaker I always acknowledge my own ambivalence toward a subject and my films always tend to be morally ambiguous in some regard, so I have no problem playing devil’s advocate and playing on both sides of the fence.

It was wonderful to see a transgender actress portray a transgender character in the film. How do you feel about the current debate about whether cisgender people should be allowed to play transgender characters?

It’s a complicated debate, and again I have to say I feel ambivalence about it. I made a short film in 2011 called Offing Jack in which two transmen play transmen and they have a sexually explicit scene. The whole point of the film was to cast two actual transmen and to be realistic and honest about their sexuality. (I listened to them in terms of what they were and were not comfortable with and how they preferred to be represented sexually.)

In 2014 I made a cinematic adaptation of Pierrot Lunaire – the Schoenberg opera that I had directed on stage – casting a cisgender woman to play a transman. The actor, Susanne Sachsse, was an experienced stage performer who nonetheless had to do vocal training for four months to prepare for the play and film. She played the role beautifully and sensitively. Now I have a film in development with a main character who is M-F and I fully intend to cast a transgender character in the role.

On the other hand, in terms of gender performance I feel like everyone performs gender all the time and part of me believes the whole point of acting is to have the freedom to play someone completely different from or even opposite to oneself. So it is a dilemma! In The Misandrists, there was no question for me that Isolde – a character who is M-F – had to be played by a transgender actor. On the other hand, one of the cisgender characters in the film is played by a transgender actor!

Call Me By Your Name recently came under fire for not showing a single dick in the entire movie. Why do you think a lot of filmmakers are still so prudish about showing full frontal male nudity in their movies?

For me the problem with movies like Call Me by Your Name or Moonlight or God’s Own Country is that they are essentially designed for straight audiences who are queasy about gay sex. In a sense they’re what I call “conservative gay films” that encourage liberal tolerance toward gays, something that I’ve always bristled at.

But it’s not just the lack of dick, so to speak. It’s the agenda of the movie – that gay is okay if it’s cultured and elevated and circumscribed, or if the gay male characters are purely masculine (effeminate gays are still rather taboo, or just disposable sluts, like in GOC), or if they are monogamous and ascribe to “family values” or even religion.

My personal philosophy of homosexuality is much more about embracing the sissies, the perverts, and the revolutionaries – fags that were at the forefront of the liberation movement and that challenge the conventions of the dominant order. I mean somebody’s got to, otherwise life would be so basic! So these films are fine for guilty liberals, but for certain gays they seem a bit tame and retro.

You love to push sexual limits in your work. Why is pornography still such a fascinating and important topic for you as a filmmaker?

Many great filmmakers – from Hitchcock to Buñuel to Pasolini – expressed a desire to make pornography. The best filmmakers for me are drawn to the taboo, to the challenge of representing the unrepresentable, to test the limits of the audience. As an underground filmmaker, I also always understood the importance of shock value and provocation, which for me are not bad words at all.

In my early experimental queer punk films in the eighties, I used porn for what I considered political purposes – going against the grain of the gay orthodoxy, which had already begun to become assimilationist – and against the punk orthodoxy, which had become somewhat homophobic and sexist. Being unapologetic and in-your-face about gay sex and showing it explicitly, especially in non-porn contexts, was and continues to be a militant gesture for me.

These days I’ve been working for porn companies like Cockyboys and Erika Lust, but also making movies that are more mainstream without explicit sex like my movie Gerontophilia. I really don’t see why a filmmaker can’t do both. I’m all about breaking the glass ceiling for pornographers!

How do you think depictions of sex, nudity, and pornography will change in this era of MeToo and Times Up?

In The Misandrists, Ute calls men “the pigs of the world.” (Editha suggests she leave pigs out of it.) But let’s face it, a lot of men are pigs! That’s what makes the over-the-top anti-men sentiments in the film so satisfying! (In the gay world, being a pig in sexual terms has more positive connotations, although obviously there are women who want their partner to be a pig in the bedroom, male or female.)

So these new movements are telling people (mostly men) that sex has to be consensual and non-coercive and that this piggy behavior has become systemic and institutionalized and should be fought against. But it can’t be an anti-sex movement or an anti-porn movement and it has to allow people their dodgy sexual fantasies.

I’ve always been in opposition to anti-sex and / or anti-porn feminists. I’ve expressed a certain ambivalence toward porn (I wrote a memoir called The Reluctant Pornographer) because I recognize that there is a dark side of the porn industry, that people are exploited and treated badly. But that can be said of any large industry or institution. (Think Hollywood or Silicon Valley.)

I consider watching (and making) porn as a ludic space of sorts, a place where people can playfully work out their dark or politically incorrect sexual fantasies. It must always be acknowledged that sex comes from a primal place and that is a force of nature that can’t always be regulated or tamed.

Culture is able to exist and develop because we sublimate a part of our sex drive and energy to pursue other less selfish goals. But sexuality must be expressed, otherwise it results in sexual repression, or even surplus repression, which can lead to very monstrous things. (Think orthodox religions.)

There are lots of women working in the mainstream porn industry who are successful and independent and in control of their careers, and dare I say feminist. There are also lots of women making porn for women or making directly feminist porn.

I’ve made three short porn films for Erika Lust Company (two of which will be released soon), a company that is totally female-centric and politically conscious, although not necessarily always politically correct. Porn per se is not the problem, as long as it’s made ethically and in the spirit of the free expression of sexuality.

With Otto and L.A. Zombie, you explored sex and queerness through the metaphor of a zombie. What was it about the classic movie monster that inspired you with these movies?

As a filmmaker – and particularly as a queer filmmaker – you have to be conscious of when you start “preaching to the choir.” Filmmakers should always be striving to reach new audiences and making genre movies or exploitation movies is a great way of doing that.

The zombie movie is a popular form, so even though I make zombie movies with explicit gay sex, the gore and “gorn” aspects of the films appeal to all sorts of weirdos of all genders! Aside from that, the zombie trope is very all-purpose, especially in the context of late capitalism. It’s about consumerism, conformity, alienation, and about things going viral.

My movie Otto is about a young, alienated gay boy who may or may not be a “real” zombie. He has internalized all the fear and self-loathing and violence directed towards him as a queer and then manifests it outwardly in monstrous form. He feels dead inside and so he starts to look dead outside.

Additionally, anonymous gay sex in dark parks or saunas is not unlike being in Night of the Living Dead! And not necessarily in a bad way! L.A. Zombie is about an alien zombie who fucks dead people back to life. It speaks to how gay sex was pathologized by the advent of AIDS and it’s a symbolic reversal of that fear and paranoia. But it’s also pure exploitation and gorn. The corrupted, post-human bodies of zombies are great for porn because you can create your own orifices!

Are there any other horror monsters you’d be compelled to explore in your movies?

Although it’s more sci-fi than horror, I’ve always loved the genre of Earth being invaded by monstrous aliens, some more insidious than others. It was used as a metaphor for the Red Scare in the fifties – the fear of a Communist takeover of America. I always enjoy depicting outsider characters, especially those that threaten the dominant order. And then I’ve been trying to write a gay serial killer script for 20 years. Hopefully that will happen someday!

You’re quite outspoken when it comes to cinema. What do you think are some of the worst films of the past year? And what do you think are some of the worst problems with a lot of modern movies?

I write a column online for Talkhouse Film called Academy of the Underrated, but I’m tired of being nice, so I’m threatening to start doing the Academy of the Overrated. The original Star Wars would be a good one to start with!

Okay, to be honest I hated The Shape of Water and CMBYN, to name two. I hate movies designed to assuage liberal guilt or to promote liberal tolerance of homosexuality. I’m bored to death with the Marvel Universe and the Star Wars franchises.

A lot of these movies pay lip service to leftist or liberal principles but they’re actually deeply reactionary. Even if there is moral ambiguity, the status quo is always reinforced and family and Christian values are promoted. They’re ultra-nationalistic and promote American exceptionalism. It’s all so jingoistic and propagandistic. Barf.

—

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.