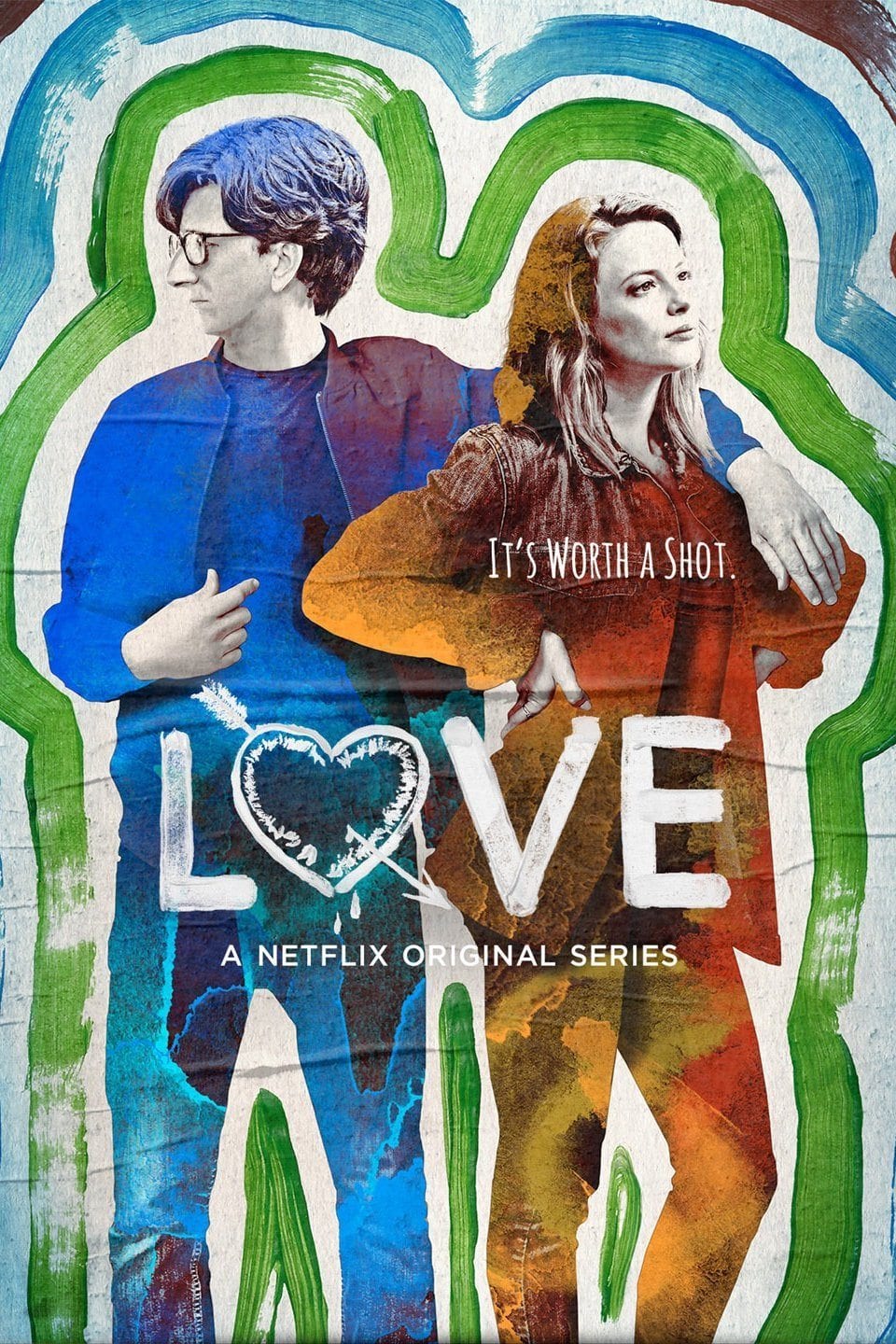

‘Love’ season two is like all great relationships

Despite being billed as a romantic comedy, Love is about as far from a frothy romance as you can get. The deeply dark, painfully authentic comedy is back today for your bingeing pleasure.

Love was a bit of a sleeper hit for Netflix; it didn’t really get dissected online and it wasn’t a social media trending topic, but it was a show that people really, really liked. As Judd Apatow said in a tweet, “Seems like people binge then forget everything about the show.”

Love season one was created by husband and wife duo Lesley Arfin (of Girls) and Paul Rust (who plays Gus on Love), along with Apatow. It focused on very real, very flawed could-be couple Gus and Mickey, whom the creators say are loosely based on themselves.

Their first episode meet-cute was anything but cute, with Mickey falling very quickly into the broken bird trope and Gus looking, at first glance, like he could be her savior. A few episodes in, we realized Gus is far from perfect himself.

What followed was an emotional attack on the viewer, following the trials and tribulations of two very maladjusted people. We suffer through writers’ room breakdowns, text message freakouts, ill-advised hookups, Andy Dick-enabled drug binges, and much more suffering on all accounts. By the end of the first season, just when we think we can’t take anymore abuse, Mickey finally admits she has a problem and Gus picks the worst ever time to make a grand romantic gesture.

Love season two picks up exactly where we left off, with Gus & Mickey trying to make sense of what just happened. Keep a cushion handy and get ready to Netflix and cringe.

Both Love seasons careen along like a slow-motion car crash, and it can be hard to pinpoint exactly what the appeal of the show is. Watching it is like an endurance sport for the viewer. Emotionally, you can feel simultaneously drained and uplifted while dragged along by a pair of narcissists for this chaotic ride.

Perhaps the main appeal is the humanity the writers infuse into these characters. Despite being severely flawed, they are realistic. These people have no boundaries. They can be manipulative and they don’t always act with the best intentions.

They have no idea what they want, but they expect other people to deliver it to them with a bow on top. However, they are genuinely trying, and though they might become even worse, we know they also might get better. And as the show progresses, we do see them learning and growing from some of their myriad mistakes.

When Love is good, it’s really, really good. Its treatment of Los Angeles is realistic: LA is depicted warts and all, with lushly shot scenes of boating on Echo Park lake, mushroom trips on the leafy streets of Silver Lake, and police lockdowns in the Hollywood Hills.

LA is a car town with a real lack of street life. Angelenos have long known that if you want to date in LA, you have to embrace meeting people in the most unlikely of places, like Mickey and Gus. In any new relationship, you also have to accept there will be some serious car time involved.

While most Angelenos probably don’t get invited to housesit their friends’ multi-million dollar mansions (episode 9), they can probably relate to Mickey and Gus’ nightmare bosses, on-set dramas, and celebrity-adjacent friends.

When Love is bad, it can truly bore. In the Gus & Mickey “getting to know you” scenes, the producers ramp up the awkward factor to 11, which, although it perfectly mirrors the stilted conversations of a new relationship, can give the viewer anxiety. I had to pop a Valium just to get through all twelve episodes.

If the show can sometimes feel like a love letter to LA, it’s also an ode to cinema. Unapologetic film references are woven throughout the show, to the point of exhaustion at times.

It’s a very knowing show in that when tropes and conventions crop up, they are either subverted by subtext or called out by characters as being ridiculous. It’s a lot to process, and it comes as no surprise Paul Rust has writing credits for Arrested Development, the most meta of all sitcoms.

The way Love treats female addiction is particularly conversation-worthy. Our society can have notorious double standards when it comes to male and female behaviors: male addiction is sometimes passed off as a rite of passage, while female addiction is often deeply stigmatized.

A theme from the first season is Mickey not truly understanding if she has a problem, or just not wanting to admit that she does. We recognize her downward spiral but understand that before she can get help, she needs to admit her dependencies to herself.

By highlighting functioning addicts, the show opens up conversation about female addiction without passing judgement. This has as much to do with Gillian Jacobs’s subtle performance as the skilled writing.

Mickey is a screwup, but she never passes herself off as anything else. Despite her destructive behaviours, her friends and the audience keep rooting for her. While in the throes of addiction, an addict can feel like everyone is against them, but the reality of the situation is that an addict’s biggest enemy is herself.

When Mickey attends Sex and Love Addicts Anonymous in season two, we twice see her making supportive relationships with other women in the program, both of whom look like normal, functioning members of society. The inclusion of these characters is a deliberate and valuable signal to young women struggling with addiction that they can seek help and be accepted without judgement in their life after addiction.

As Gus and Mickey’s relationship unravels, so does our understanding of everything we thought we knew about these characters. Both antiheroes have anger issues, and Gus’s codependent tendencies really start to show from episode 9 onwards. Mickey comments: “Sometimes I feel like I’m his fixer-upper.” What holds the viewer’s gaze is our (tenuous) prurient interest in watching things fall apart.

The weakest parts of the show are the subplots involving friends and colleagues orbiting Mickey and Gus’s lives. Though these feel tiresome at times, they do work to juxtapose the fiery dynamic of the central couple. Gillian Jacobs and Paul Rust’s chemistry snaps, crackles, and sometimes pops in their shared scenes.

Love season two ends with the central couple not much further on than where we left them last year: still lying, still emotionally stilted, and still immature. In the season closer, Gus and Mickey have got to talking the talk, but only season three can tell us if they are ready to walk the walk.

For all their faults, these characters are not irredeemably awful, and just like your real friends, we have hope they’ll change, learn and grow from experience. Watching them evolve might be a painful process, but by digging into their complexities we might just learn something new about ourselves.