An interview with Jeanne Geoffray

As the shadows of history gather to recount the valorous tapestry woven by Alice Geoffray, her indelible ink of activism and education continues to inscribe itself upon the annals of time.

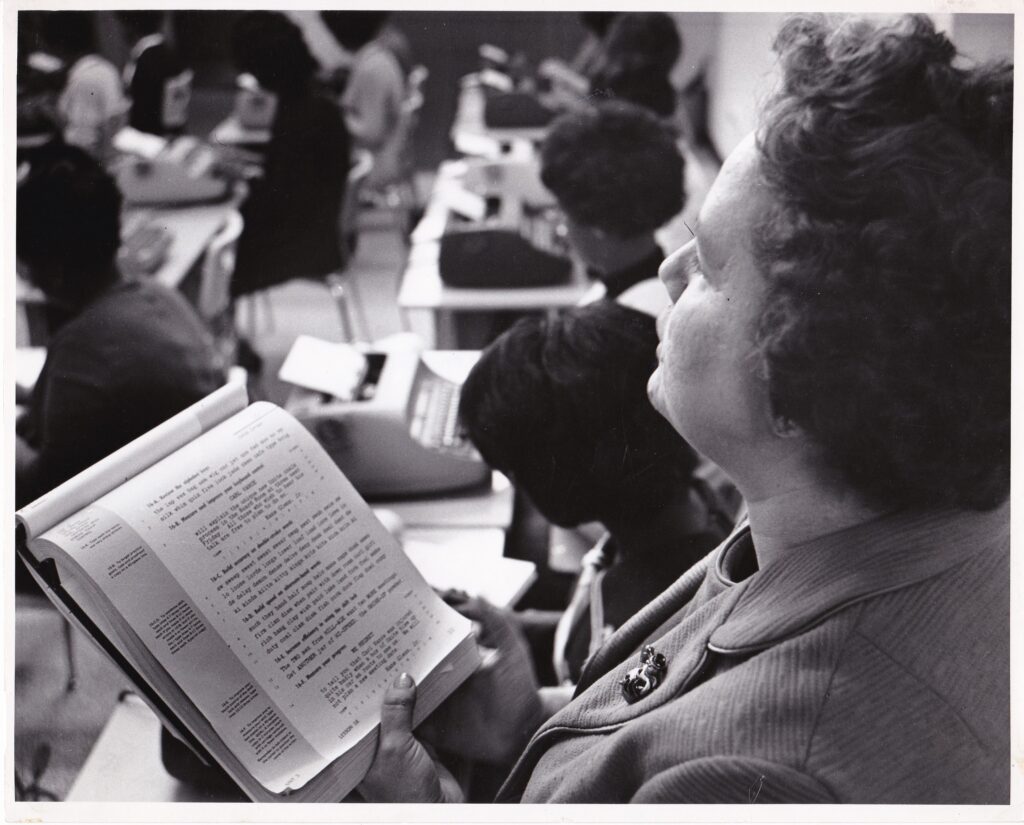

Jeanne Geoffray, the living testament of Alice’s intrepid legacy, unravels an epochal tale that is an elixir of inspiration, and a bridge spanning across chasms of inequity. The Adult Education Center, where Alice dedicated her soul, was not merely an institution; it was a crucible where the iron of resilience clashed with the fires of segregation, giving birth to an unyielding blade of empowerment.

Jeanne, with the fortitude of her lineage and the echoes of a half-century-old revolution resonating in her spirit, carries forward the sacred ember kindled by her mother.

Through her unwavering commitment to share the stories that are the strands of this tapestry, she dares us to look beyond the mists of time and engage with history not as a bygone whisper, but as a clarion call that reverberates through the hearts and minds of generations to come. With a tenacity that cradles the grace of her ancestry, Jeanne Geoffray is both a guardian and a scribe of a story that transcends mere words.

Jeanne, why do you think your mother’s story of activism and education is so important to share today, more than a decade after her passing?

I was thirteen when the Adult Education Center (AEC) opened its doors. Mom would come home — late at night — and tell us about her day, especially stories about the students. Mom had a way of pulling you into her stories and feeling connected with the students.

I knew it was a story that needed to be told then and thought about her story over the next fifty-five years. After so many years I was afraid too much time had passed for us to reconnect with Mom’s students to hear their stories first-hand but that was far from the truth.

When my brother Jeff and I embarked on our journey, it was my job to reach out to as many of the 431 graduates as we could find. Each graduate welcomed my phone call with open arms and I spent hours and hours with them as they told me how the AEC had changed their lives and the lives of their family.

I was so uplifted by each and every story and knew others would be too. Jeff and I HAD to tell the story as so many of the stereotypes that are still used to divide Americans, Black and White, rich and poor, will be shattered.

Can you share some insights on what it was like growing up with Alice Geoffray, an incredible woman breaking barriers in a time of immense social unrest?

It was exciting but chaotic being one of seven children. I knew Mom was doing incredible work and we were so proud of her. The school was often in the newspapers and on television. For me, the most profound emotion I can remember is seeing and feeling my Mom blossom throughout those seven years at the Center. That is what stood out for me the most. I truly was in awe of her even at an early age.

To this day I do not know how she maneuvered through each day, keeping us grounded as well as working a full-time job. But it’s important to mention that Mom’s career would not have been possible without Ms. Midred Cayette, our domestic worker, who took care of our family while Mom was at work.

With Mom working late six and sometimes seven days a week, it was Ms. Cayette, and later two other domestic workers, who were there for us when we returned home from school. This fact played out in homes across our nation as White women and men advanced their educational and professional careers thanks to the diligence of domestic workers who did not earn a pension or even social security in their work.

The last episode of the podcast, A Cowardly Lion (the title refers to Mom) is largely about the relationship between Ms. Cayette and Mom’s career. That episode is an example of how our series opposes the kind of stereotypes told in stories like The Help.

Jeanne, how do you feel your mother’s work in education, especially in the civil rights era, has influenced your own life and career choices?

I formed an opinion early on – both personal and political – about standing up for people of color and other common-sense democratic values. I felt it was a privilege at that time to be a small part of the world of Mom’s students and feel the same now. I felt in my bones it was the right thing to do.

I remember vividly Mom getting word that the KKK was going to burn a cross in our front lawn. She gave us warning but we were never really afraid. In fact, Mom said that it may be a blessing since the light on the porch had burned out. No hysterics…just a joke to make us more at ease.

As it turned out, they did not come. I was a little disappointed (never shared that with anyone!) as I knew that would bring more attention to the school and what she was trying to accomplish with her educational program.

Your mother was a pioneer in educating African-American women at a time when segregation was the norm. What lessons from her journey resonate the most with you?

Stick your neck out. Mom’s favorite animal was a giraffe and often thanked people for sticking their necks out to support her and her educational goals. Jeff and I adopted this philosophy and started a Giraffe Club for people who have supported us as we truly appreciate them for believing in us.

In our family, if you asked each of the seven children about who was Mom’s favorite, each would think it was them. At the AEC reunion in 2018, this came up with the students. Each one thought they were Mom’s favorite student. Everyday I try to achieve that same thing. I try to make a person feel important when they are around me.

The transition from business to producing a podcast and book is quite a leap. What prompted you to make this change and how has it been so far?

Always wanted the story to be told. And, with Jeff at my side and with his talent, it was possible. He pushes and inspires me each day as Mom did by devoting so much of his time and energy to something we both feel is important.

I am an example of being a life learner as each day we learn something new whether we want to or not!

How do you think the story of Alice Geoffray and the Adult Education Center will inspire today’s generation?

Through our 431 Exchange scholarship winners we know the AEC story is inspirational to a new generation. Before we meet them on their Zoom interviews, they get an opportunity to visit our website to see what our legacy is all about. Their reaction in thank you notes, follow-up emails and on Zoom express how much the story inspires them.

The scholarship committee is composed of myself, Jeff and alumnae of the AEC. The scholarship applicants’ reaction and interaction with the women they have read about are usually emotional. Applicants typically say, ‘the women that I read about are so incredible and I wish I had courses like they did in my high school.’ One scholarship winner introduced us to her Mom.

Her mom had taken such an interest to find out more about our mom and the graduates. So, not only do we know a younger generation is interested, we know they spread the word through their storytelling about us. Another scholarship winner introduced us to her grandfather who at first was so shy at our event.

Then, learning more about the graduates, he blossomed and told us his story about his wife during that era. An important goal of our podcast is to inspire a younger generation to seek out the biographies of their parents and grandparents.

The Adult Education Center had a remarkable placement rate, placing 94% of its graduates into jobs with high salaries. How did your mother’s innovative teaching methods contribute to this success?

Jeff spoke about how the teaching of both hard and soft skills made the program unique and contributed to the students succeeding on their path. But, the program’s approach to marketing the students on an individual basis truly set it apart. As a business teacher my mom had a talent for finding professional ways to champion her students even before the AEC.

She was a marketing machine with creative ideas that was focused on spotlighting a student’s skills and personality. This process began before the students even graduated. She and James Coleman made it a point to involve local businessmen in the school. Notable members of the business community, and politicians, visited the school to lecture, meet, mentor, and conduct mock interviews.

In many instances these mock interviews and other interactions led directly to job offers. When they did go out for formal interviews, each student had a brochure that introduced potential employers to the school’s rigorous program along with the students own accolades.

Potential risks of hiring the students, such as the fact that some were older adults with children, were mitigated by talking up qualities, such as maturity and commitment, that could help overcome those same objections. It was this attention to the special qualities of the individual student and the needs of employers that made the school so successful and the students so seen and employable.

It also contrasts the notorious track record of the many for-profit vocational schools and colleges that would come and go (bankrupt) over the following decades and saddle their students with debt without providing them with profitable careers.

Your mother’s work was recognized nationally. Could you share some memorable reactions she received for her efforts?

I was only twelve when Mom won her first national award – The Valley Forge Classroom Teachers Award. That was a big deal and it put her on a path to meeting Father Gibbons and getting involved with the AEC. Even before that award, her students were featured in a number of newspaper articles. Mom had a knack for designing programs that would catch the eye of journalists and the public.

In fact, that was sort of her point in coming up with imaginative ideas, so that it would attract attention to her students and their achievements. Throughout her life at every career point, she would be recognized. I learned this through personal experience.

In high school when substitute teachers found out “a Geoffray” was in class, they would single me out to tell me how wonderful a teacher my mother was. This happened time and time again. In the 1980’s, a renowned TV journalist, Angela Hill, aired a feature program called Quiet Heroes and Mom was the first one spotlighted. That really summed her up…a quiet hero.

The phrase “we exchanged a life of poverty for a life of prosperity” sums up the transformation that many students experienced. Can you elaborate on this idea?

Over and over again as Jeff and I speak with the graduates, we hear how the school transformed their lives and the lives of their children. They were proud of the hard work they put in to create a future for themselves. They were proud of the speech classes they attended. They were proud of all of the skills they acquired and continue to use. Many many retired from the job they landed after graduating.

Fifty plus years after the AEC, we now have the statistics of how successful their lives have been. As Mom would say, “they worked happily ever after.”

How did the Adult Education Center’s curriculum enhance not only students’ technical skills but also their self-esteem?

Early on our Mom had an interest in increasing her students’ self-concept by taking a humanistic approach to instruction – an approach that is concerned with the well-being of the student as much as the acquisition of technical skills.

Her hypothesis was that over the course of the program, a humanistic approach would increase her students’ self-concept and that would, in turn, result in them learning faster and landing the kind of jobs they aspired to obtain.

Eventually, she got the approval of the AEC Board of Directors to invest in a third-party evaluation of the students’ self-concept both at the time of enrollment and then again at graduation. The out-of-state company chosen was recognized for designing a self-concept test that was the standard in its field.

Ultimately, the testing showed a remarkable increase in self-concept by the time of graduation; in fact, the highest increase over a nine month span they had ever seen.

Mom believed it was the combination of hard skills instruction (shorthand, typing, speech class, math, etc.) and soft skills (personal dynamics, creative writing, communications, current events, mock interviews, and African-American History) that helped the students’ self-concept scores improve.

In other words, increased their ability to understand the relationship between how they see themselves versus how they are seen by others. That is the essence of self-concept and how it is different from self-image. Someone with a healthy self-concept has a grasp of how their view of themselves relates to how they are viewed by the outside world.

For instance, how they view their own abilities compared to how an employer or job interviewer might view them. An individual with a strong self-concept has the tools to align their image of themselves with the opinion of others should they choose to do so.

A person with a healthy self-concept is not afraid to be self-critical. To have a healthy self-concept, one has to have the confidence to realistically assess one’s own abilities so that, if there is a deficiency, they can take the steps to improve. The AEC strived to give their students that confidence via its curriculum. But, also by way of a stimulating, nurturing and respectful environment.

As bell hooks, author of Teaching to Transgress, might have said, the teachers believed in education as an expression of love and freedom. One graduate spoke for many students when she said, “before the Adult Education Center they had only their family and church to guide them.”

Alice Geoffray’s influence was profound, leading to various “miniographies”. Could you share some of these stories and their significance?

Hilda Jean Smith (episode 2 of the Podcast series): A day after her wedding, sixteen-year-old Hilda Jean Smith’s mother dies, leaving her the responsibility of raising ten younger siblings. She drops out of high school and over the next years has six children of her own. Out of necessity, she makes her way to a Job Placement Center and the job offered to her was that of a cook.

She said…NO, I cook all the time for people. They then offer the opportunity to apply at the AEC for secretarial training. With all of that on her plate, she is required to go to night school to obtain her GED. Today, at the age of 75 she is employed full-time and has been accepted to a Ph.D. program in nursing. Hilda, a very religious woman with a Masters in Divinity, refers to our Mom as Mrs. God.

Sandra O’Neal (episode 8 of the podcast series): Sandra was a star student in high school until her sister fell ill. While her mother tended to her sister full-time, Sandra decided to go to work to help her family avoid eviction. On the eve of her high-school prom, she had to sacrifice school which she loved for a full-time job to help support her family.

Years later, in the search of continuing education, Sandra met Alice Geoffray. Sandra was shy but with the backing of the school, faculty and counselors, she blossomed. Like Hilda, Sandra went to night school while attending the AEC to get her GED. She, too, went on to higher education and eventually obtained a Ph.D in social work from Jackson State.

Alice Geoffray’s resilience led to the school’s revival, and this was documented in the Emmy Award-winning 1968 documentary, “The School That Would Not Die”. What impact do you think this had on public perception of the school and its mission?

In the Black community, it solidified that this was a program unlike any other job training programs at the time. Watching the film on a Sunday night with her mother and four small children, one graduate tells us that she related to one of the adult students with children being featured in the film as she had four children as well. She said…if she could do it, I could do it.

Her mom supported her by letting her know on that night if she got accepted she would help take care of her children so she could attend the school’s intensive program full time. As one graduate said after attending several ineffective training programs, “what was promised by the AEC was given.”

As many job programs across the country had a reputation for being ineffectual, this was an important message along with the message that ‘ordinary women’ could transform their lives via education.

In the process of saving the school, Alice had to assert herself and lead in a male-dominated society. How do you think this experience changed her?

She quietly gained confidence through her work and her writings to take on the big challenges of the school. One Black executive from AT&T, Edgar Porre, approached my mom to help him with a tax campaign to raise taxes for the school system. With everything on my mom’s schedule, she still said ‘yes.’ Edgar said, he and my mother, would until the early morning hours to get the work done.

Edgar was successful and the taxes were raised for schools. Edgar became a regular visitor at the Center by lecturing to the students about the business world. He still remains one of Mom’s biggest fans and he has adopted us as our Uncle Edgar.

When the school closed and Mom eventually accepted a job at the State Department to head up the new division of Career Education, she was not really welcomed with open arms. Being a quiet worker with no ego, she offered on the first day to help type and write for the other executives.

Working side by side, they got to know each other and before long they realized this is truly a woman I want to work with. She earned her reputation and has been called the “Mother of Career Education” in the state of Louisiana.

Her indefatigable strength was sharing her knowledge and talent with co-workers, bosses, family and friends.

Alice Geoffray was a recipient of many honors and acknowledgments. Could you share a bit more about how these accolades affected her personally and professionally?

As a writer of successful business books, she was asked to be a keynote speaker to a large audience at a national book convention being held in New Orleans. The organizers of the convention had not met her beforehand and knew of her only because she had authored five popular text-books on business education and communication skills.

They had only talked with her over the phone and had communicated mostly through written correspondence.

To set the stage, Mom was overweight, did not spend much money on her wardrobe, and could easily play the part of the archetypal grandmother in any Hallmark movie. She walked into the hotel from the nearby bus stop with her briefcase which happened to be an NPR promotional bag.

Upon shaking the hands of the organizers, she could immediately see the worry in their faces. “Who is this lady?” “Was she going to be good?” “Did we choose the right person to give a speech on, of all things, business education?”

Well, their fears were soon relieved. My mom began her speech and eventually had the audience alternately laughing and crying from practically her first words. In her work, she had gathered through first-hand experience thousands of stories about the heroic struggles of students seeking jobs — and succeeding — with the help of competent and caring career counselors and teachers.

Those educators could only perform their jobs well because of the kind of materials her audience published or purchased. Mom knew how to tell her stories in a way that was both entertaining and substantive.

I truly loved Mom’s frumpy look as it caught people a little off guard. I experienced over and over during her life how people discovered her talent for themselves and then would admire and appreciate all she accomplished. After the convention, Mom was asked to give other keynote speeches across the country for the same company. The travelling that was entailed did not fit her schedule but she knew she had won them over.

With Alice’s story finally being told, how do you hope this will impact future generations and their understanding of the civil rights movement?

For the younger generations, it will be a different, uplifting story about women wanting to land that first professional job and putting everything on the line to get it. I am still amazed that these women would attend school from nine to five, go home (and many to their children), do hours of homework, and then be back again the next day.

One student lived outside of New Orleans and had to take a Greyhound bus back and forth to the school each day. And, after the school day, before jumping on the Greyhound, she took a bus to attend night classes to get her GED. Attending the two schools, and travelling back and forth and in-between, every day was an eighteen-hour day for nine months.

It would have been an even longer day if not for a man who met her at the Greyhound bus stop after midnight to drive her home. Fifty years later, the graduate’s chauffeur, accompanied her to the 2018 reunion.

Your mother started writing a book about the school and its students but never finished it. What do you think was the reason behind this?

She always wanted to finish it. I remember her spending the most time writing and rewriting the first chapter. She wanted to pull the reader into a time when she felt so hopeful. A time when she thought everything was possible.

It was hard for her to come to terms with the fact that she could not have the kind of fairy tale ending she had envisioned at the beginning. In retrospect, the problems she, her fellow teachers, and her students had fought so hard to overcome still persisted.

Can you tell us more about the book and podcast series on the life of your mother and the legacy of the 431 Exchange? What can readers and listeners expect?

The stories we tell on the podcast are truly inspirational and have only become richer over time. When you hear their stories, you will want to get to know the graduates better and secretly wish they were your sister.

Jeff and I want to be a part of their family reunions, or have a Thanksgiving Day meal with them, and we think audiences will too. In an age where so many heroes are manufactured, the women and men depicted in our podcast are worth getting to know and even studying.

How does it feel to be able to carry on your mother’s legacy through your work with the 431 Exchange nonprofit and the book and podcast series?

It has been the most uplifting five years of my life — to be able to work on a daily basis with my brother, Jeff, the graduates, and the scholarship winners. The love the graduates show us each and every day has come as the most pleasant of surprises at this stage of our lives.

Given the chance to speak to your mother today, what would you like to say to her about the work you and your brother have done in continuing her mission?

I would enjoy having a conversation with Mom to tell her how Jeff and I fell in love with her graduates just as she had when they were at the school. And, to tell her we have the same feeling about our Scholarship Winners who are carrying on the legacy.