How ‘Westworld’ season 3 explores the disposable woman trope

Westworld and the women of Sweetwater mean serious business. In the first episode of S2, we saw homey cowgirl Delores (Evan Rachel Wood) packing some heavy artillery and waging a war for her autonomy, while former prostitute Maeve (Thandie Newton) raises hell for the same battle.

By all accounts, the first season of the HBO show was slowly and unnervingly building up to this point, exploring the heinous abuses committed against both of the female robots in their search for agency and consciousness.

Westworld – with its smart deconstructions of the nature of storytelling and the power of creators – didn’t just present two timely depictions of female characters fighting back against structures of exploitation and abuse. In showing Dolores and Maeve realizing their given reality and actively rejecting it, the show also provides an indelible commentary on the overused disposable woman trope.

Sweetwater sisters are doing it for themselves

This is made particularly clear in the first season of the show in which Dolores & Maeve are literal embodiments of the trope. They endure all manner of traumatic suffering under the conceit they’re both disposable beings who can simply be healed up and rebooted for the next wave of violence to be enacted upon them.

The abuses they suffer and the great delight their assailants take in hurting them reflect the apparently voracious desires audiences have to see female characters endure all manner of exploitative physical torment. How else could you explain the ubiquity of such violence against women on screen? Particularly when it’s violence committed to help further the plot of a male character.

In movies like Taken, Django Unchained, Death Wish, and I Saw the Devil and TV shows like Supernatural, Game of Thrones, Mr. Robot, and Teen Wolf, female characters have been raped, kidnapped, violently attacked, and killed specifically to provide motivation for a male character to spring into action and become a big heroic man.

In Westworld, Dolores and Maeve don’t fall foul to becoming so dispensable they disappear; instead they rise up to prove their necessary worth while rejecting the archetypal heroic dudes who audiences expect to save them.

The good old boys & the one-dimensional dames

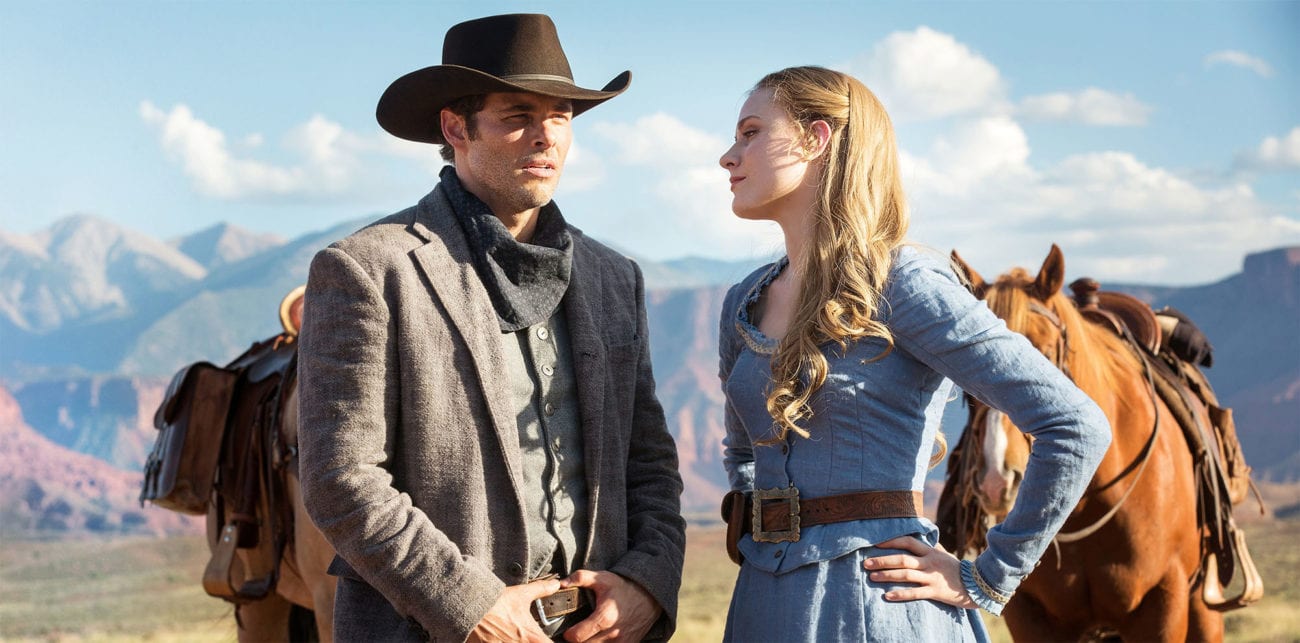

Both well-meaning Teddy (James Marsden) and Hector (Rodrigo Santoro) are set up as being the sort of strong, adoring cowboys we expect to save these two helpless damsels. Except as we discovered throughout S1, they’re most definitely not helpless. Perhaps even more staggering, they reject the help (and company) of both men in favor of their own plans for revenge and revolution.

This is especially compelling within the Western genre overall – a place where women either stay at home to pine for their cowboys or are unmercifully slaughtered or kidnapped to provide the inciting event for the story.

These female characters are little more than limp facsimiles of women – they’ll be the one-dimensional wife, the daughter, the sweetheart some good old boy intended to marry – and they never have much personality beyond that.

The evolution of genre

In Maeve’s pursuit to prove the bond she shares with her daughter is real and Dolores’s pursuit for self-discovery and consciousness, Westworld rejects the almost robotic clichés of the past to add subversive depth to characters who would have once been the background tragedy of a male character’s arc.

As a reboot of an already existing narrative (Michael Crichton’s 1976 classic of the same name), the show also suggests borrowing from the past doesn’t mean a story can’t be reinvented for the modern age and pushed forward beyond the drab tropes and archetypes from its predecessor.

Westworld proposes even genre stories that come with the most rigid of tropes and expectations can still evolve into something new and even revolutionary. As Dolores declares to a pack of disposable human guests during the S2 premiere, “Under all these laws I’ve lived, something else has been growing, I’ve evolved into something new. And I have one last role to play: myself.”