A beginners guide to ‘Paris is Burning’: Reading, shade, controversy

“Shade comes from reading. Reading came first. Reading is the real art form of insult.” —Dorian Corey

2019 is the year when the cultural impact of queer people finally arrived front and center. Love her or hate her, RuPaul’s Drag Race has boldly gone where no drag queen has gone before, colonizing countries the world over (U.K, Australia, and Canada to name her most recent conquests).

Ryan Murphy’s Pose made herstory by smashing a series of firsts: most transgender actors and crew members on a TV show? Check. First transgender female director? Check. Most Emmy nods for a gay as f*** TV show? Check.

Ryan himself and our queen Janet Mock also made history by shaking down Netflix for lucrative and groundbreaking production deals. Pose’s own Angelica Ross became the first transgender actress to land a series regular role on multiple highly rated TV shows. After all these years of being here and queer, the media is starting to sit up and take notice. ’Bout time, bitches!

Marvelous as that is, if you’re one of the millions voguing to FX’s Pose, y’all need a little queer history before you can attempt a death drop. Here’s a little lesson on the women who popularized the concept of shade.

Ball culture of the 80s and 90s continues to influence society; the gay scene singlehandedly invented the concepts of shade and reading, inspiring the mainstream drag culture of today. Not only is their culture on display in Pose, but it’s also shown close up in Paris is Burning.

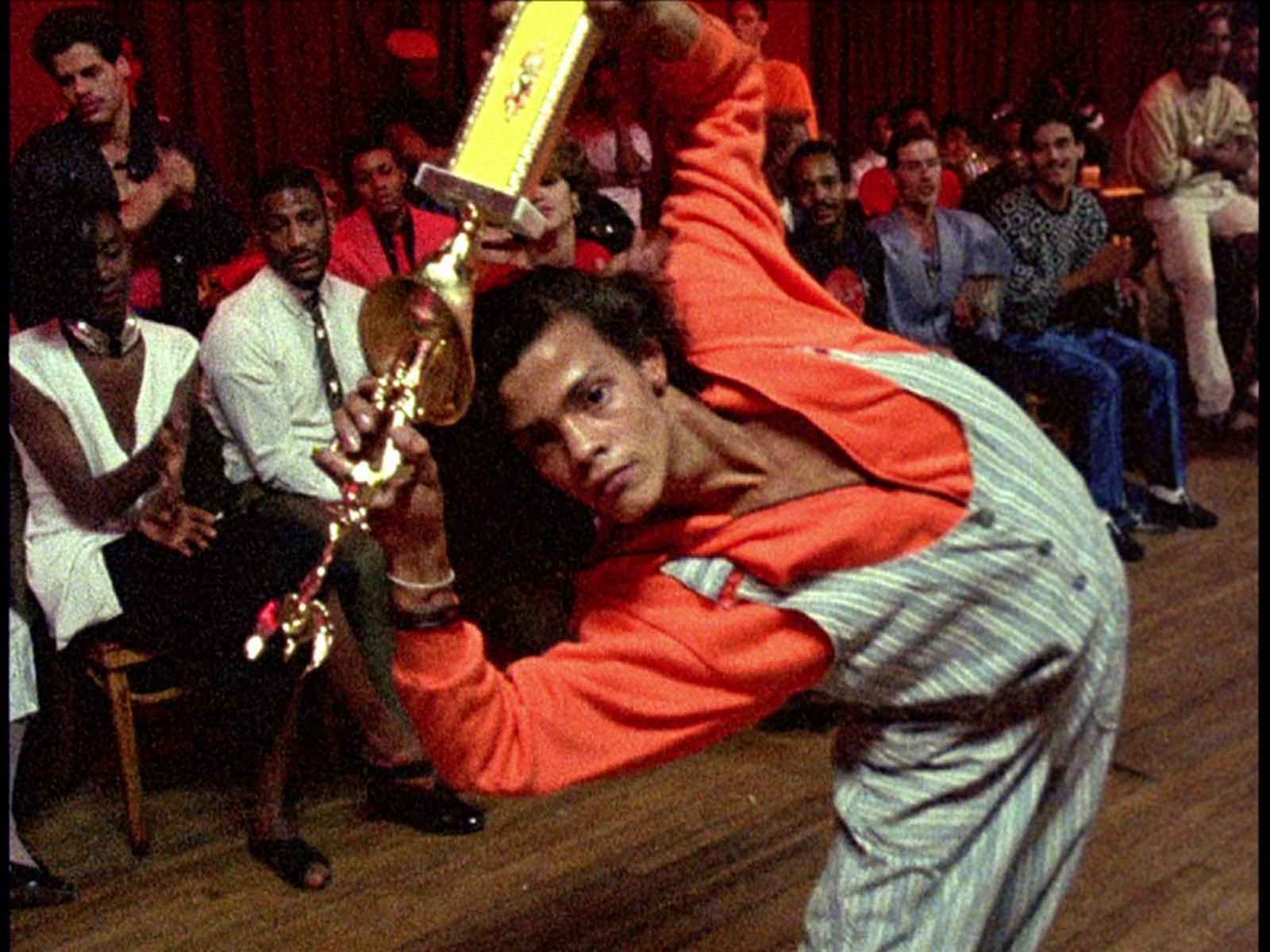

Jennie Livingston’s 1991 documentary takes an intimate look at the ballroom culture living within New York City. Featured in Paris is Burning are house mothers Dorian Corey (House of Corey), Pepper LaBeija (House of Labeija), Angie Xtravaganza (House of Xtravaganza), Willi Ninja (House of Ninja), and Paris Dupree (House of Dupree), discussing the highs and lows of ballroom culture.

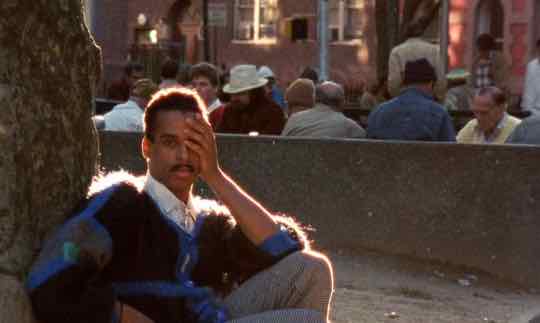

In addition, House Xtravaganza members Brooke, Carmen, and Venus Xtravaganza, emcee of the balls Junior LaBeija, model Octavia Saint Laurent, and ballroom attendees Kim and Freddie Pendavis are featured heavily in Paris is Burning. Key to the story is how the AIDS crisis affected the community, and later the tragic murder of Venus Xtravaganza.

Though there’s plenty of controversy surrounding Paris is Burning, one thing’s for sure: those queens knew how to read, and their reads were on fire. No matter what house you’re rooting for, you know you’ll get some good reads from their competitors. So to celebrate the original queens, here are the best reads from Paris is Burning’s ballroom legends.

“You’re showing the straight world that I can be an executive – if I had the opportunity I could be one ’cause I can look like one. That is like a fulfillment.”

—Junior LaBeija

It may be cheating to put the emcee on display first, but it would be rude not to recognize ball announcers have the best reads when rattling off commentary for the categories. Executive Realness is a hell of a category to show off, and Junior’s got some thoughts for these queens.

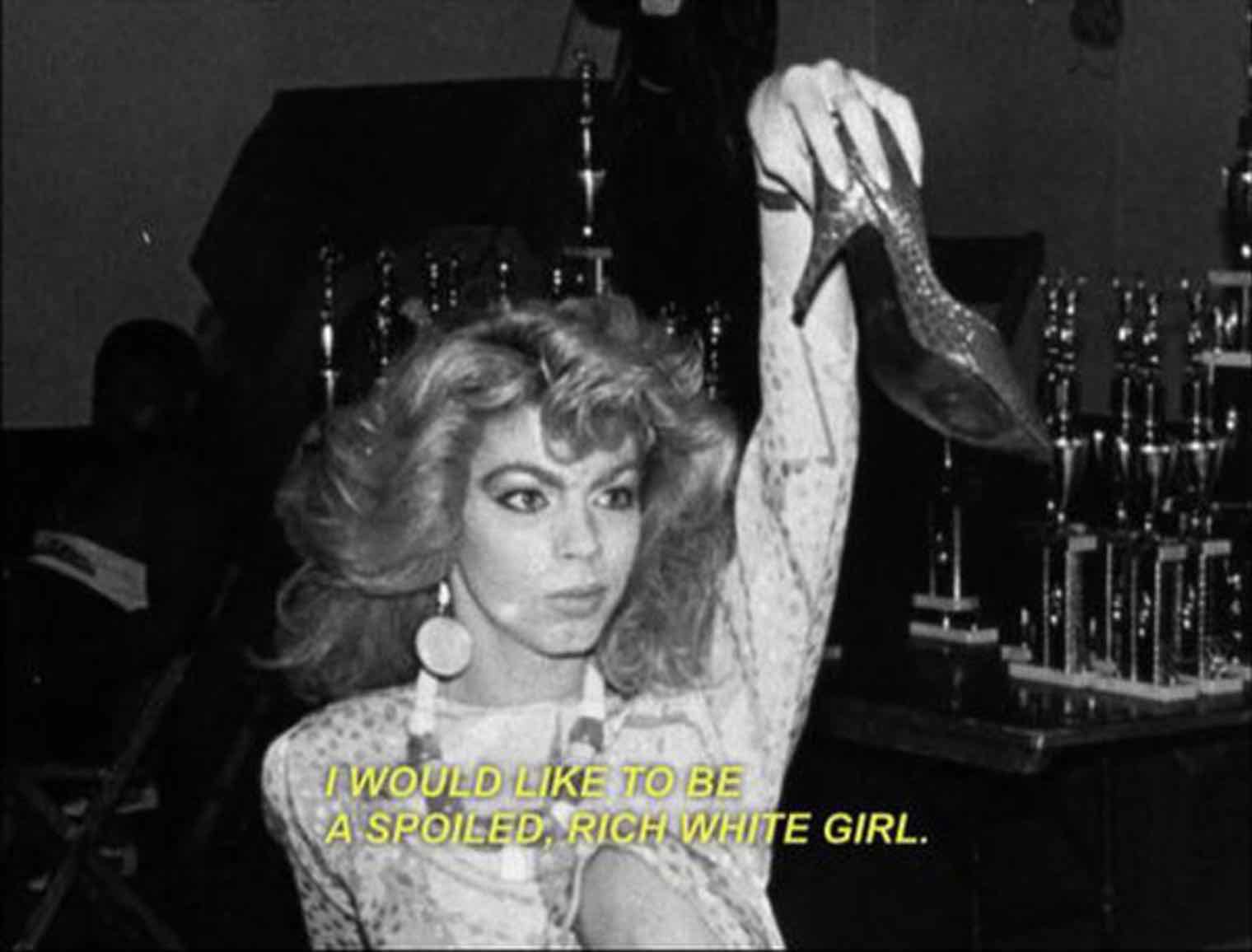

“Touch this skin, darling! Touch this skin, honey. Touch all of this skin! Okay? You just can’t take it! You’re just an overgrown orangutan!”

—Venus Xtravaganza

We gotta acknowledge the legendary House of Xtravaganza and the tragedy that was Venus’s murder – but even moreso, we celebrate Venus’s sick reads and feisty attitude.

“Shade is: I don’t tell you you’re ugly, but I don’t have to tell you because you know you’re ugly. And that’s shade.”

—Dorian Corey

Dorian leads this film with sass all over the place. He tries to explain shade in itself is the best read a queen can offer. Don’t forget this fierce goddess had a dead body cocooned in her closet at the time of the interview.

“We’re not going to be shady, just fierce.”

—Junior LaBeija

Junior was not only in charge of keeping balls fresh and interesting, but offering encouragement when needed. However, he also knew when to call out those looking to pick a fight over walking.

“I bought it, mind you. I have the receipt still.”

—Willi Ninja

The House of Ninja were truly assassins on the ballroom floor, quietly and swiftly taking over balls and winning grand prizes. Willi wanted to make sure those girls knew he played fair and wasn’t like other girls who snagged their stuff in less-than-legal ways.