Sci-fi auteur to watch: Justin Petty on ‘Nothing Really Happens’

In 2000, a 15-year-old boy in a high school film class in Texas watched Darren Aronofsky’s Pi, and suddenly understood what he wanted to do for the rest of his life.

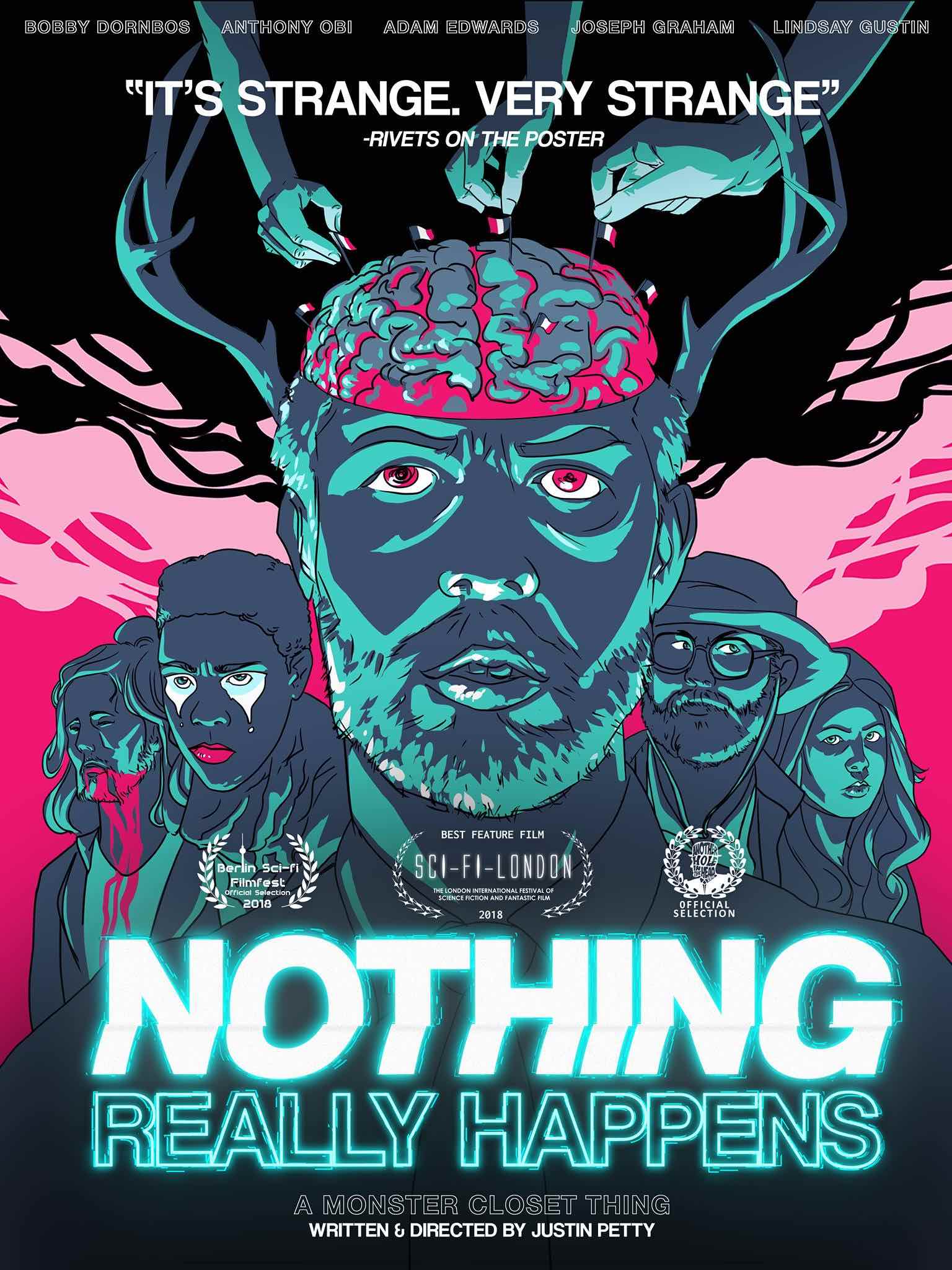

That moment led Justin Petty to pursue filmmaking and brought him to today, when his first film Nothing Really Happens has been making waves at sci-fi festivals. The film has brought the heat on the competitive festival circuit, winning Best Film at the 2018 Sci-Fi London Film Festival.

Once Petty learned that film can be more than entertainment, he knew what kind of filmmaking style he wanted to follow. Petty climbed his way up the ladder, working in video production in various capacities since college. While at one of his early jobs, he met his producing partner Joseph Graham, and the two hit if off immediately.

Petty’s debut Nothing Really Happens emcompasses the filmmaking style he dreamed of, combining sci-fi, comedy, and suspense to explore the madness of everyday existence. The film focuses on Dave, played by Adam Edwards, “a 30-year-old mattress store owner who becomes increasingly untethered in a strangely off-kilter world”.

Nothing Really Happens may be Petty’s first film project, but he’s brought his otherworldly perspective to commercials and music videos within the Houston area through his production company The Monster Closet for a while. Petty has an eye for taking the ordinary and making it supernatural and alien.

We were lucky enough to interview Petty and get the 411 on Nothing Really Happens, and what’s upcoming for him and his partner Graham.

Tell us about your history as a filmmaker. How did you start your journey?

I was about 15. I think it was around 2000 – 2001. I took a film class in high school so I could learn how to edit the awful skate videos my friends and I were trying to make. Teenage suburban kids trying to imitate Jackass. They were really bad. I had no interest in filmmaking beyond that at that point.

One day, we watched Darren Aronofsky’s film Pi in class and it changed my whole perspective on movies. I’d never seen anything so raw and inspiring before. I remember how real Max’s anxiety in the film resonated with me. It made me uncomfortable, but I was drawn to it.

I’d never really considered movies anything more than entertainment until then and I think it might’ve actually been the first film that caused me to have an emotional response. Pi flipped a switch and I just wanted to consume as many more films as possible. It wasn’t too long after that I knew I wanted to be a filmmaker.

Who were your early influences?

After Aronofsky opened my eyes, a buddy lent me Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels. Ritchie’s character creation and interactions were really fun to me. It was rooted in this gritty gangster reality, but with this layer of silliness over it. I stumbled upon Tarantino around then, as well.

I was 17 at the time, so I guess that’s pretty typical, though it wasn’t necessarily the hyper violent content that drew me in. I’m a sucker for witty, well written dialogue and absurd juxtapositions. Those guys just hit me right in the sweet spot, so I started to seek more of that out.

Charlie Kaufman and Paul Thomas Anderson films really struck a chord with me. I remember being so blown away that something like Being John Malkovich could even exist, and Punch-Drunk Love is still one of my favorite films.

How was working on Nothing Really Happens? What did you learn from the experience?

It was long and exhausting. It was also incredibly rewarding, hilarious, and fun. It took us about a little over three years to finish the film, from the day I started writing it. I think we learned how to make a film in the worst way possible. I’m half kidding, but we probably made every mistake possible along the way.

With such a small crew and all of us doing multiple jobs at once, sometimes little things would fall through the cracks. We had such a small budget that I thought we could get by without having an AD. That was a mistake that would’ve saved us quite a bit of time and headache.

I learned a lot through the process of making this film, and looking back I wouldn’t change a single thing. For all the stress and doubt that would continually creep in, I just kept reminding myself, “All that matters in the end is what shows up on that screen. As long as you get that part right, the rest will be okay.”

There were also many wonderful things that came from the numerous long nights of bonding with our little crew of four. I’ll carry those friendships and memories with me for the rest of my life.

Tell us about your career before film.

I’ve worked in video production of one form or another for my entire career. I met my creative partner Joseph Graham while working in sports video in Houston shortly after college and we started making crude comedy shorts together for a few years.

I guess we eventually got to a point where we wanted to take things a little more seriously. That led to us making several music videos for some Houston artists over the next few years, while also trying to focus on some bigger, more meaningful projects.

Where did the concept come from for Nothing Really Happens?

I’ve always enjoyed thinking about what happens between the scenes – the small moments that often don’t warrant their own screentime in movies. What weird little quirks do people have when nobody is around? What do people really do in their most vulnerable moments alone?

Life is a really strange thing and how we choose to navigate it within those mundane moments can be just as interesting as the meaningful snapshots films give us to further their plot points. I also find our frequent failures of communicating with one another in an effective way a really fun thing to play around with.

I have a casual interest in reading about nonsense snake oil-type pseudoscience and I thought using that as a sort of a narrative framework would play really well into some of the themes already being built, while adding a bit of a lo-fi sci-fi element.

Tell us about your creative process.

It usually starts with a weird interaction or awkward situation I may stumble into – or even just thinking about how a normal conversation I had could’ve gone wrong and gotten weird. I get lost in my own head often and tend to overthink things a lot, playing out numerous ridiculous scenarios that usually have no basis in reality.

This leads to countless random notes saved on my phone, based on these thoughts. Sometimes those turn into scenes. I love the strangeness of conversation, so for me that’s kind of where it all starts. Sometimes I’ll write a scene or series of scenes without any real idea what they may lead to, just because I had a fun idea of how to play with dialogue in a weird thing that happened.

I don’t always have an idea how things I write will end until I get there. I also often write out of order as scene ideas or random thoughts come to me, then connect the dots later. It’s scattered and probably not the best way to write, but it’s how my brain works, I guess.

What tips do you have for new filmmakers?

Take stock of who and what you have available to you. Write around these things and make something you think you can realistically accomplish. Don’t get caught up chasing shiny objects. Invest in yourself and strengthening your skillset over buying expensive gear. It’s your knowledge and technique that makes you a good filmmaker, not the camera you own. Make things for yourself and never stop doing that.

You were very hands-on with this project. How hard is it wearing all the hats?

It’s definitely a challenge. Making Nothing Really Happens was kind of a trial by fire situation and, while there’s definitely a sense of accomplishment once you finally finish, you’re also very aware that it nearly killed you to get there. I love so many aspects of the filmmaking process, but I think delegating a bit more and investing more into our crew is going to be a smarter move for my health and sanity.

What’s your next project?

Joseph and I have a few things in the works. Without giving too much away, he’s heading up a horror anthology idea we’re trying to put together with a group of filmmakers. We also have a few shorts we’re hoping to film in the fall and a couple sci-fi scripts we’re working on.

What’s your filmmaking mission? Name the most important thing you want viewers to experience when watching your movies.

I think first and foremost, I want them to have fun. Hopefully they’re able to escape life for a bit and enjoy something different and probably a little strange – maybe also finding small nuggets of relatability at times, while stripping away some insecurities and judgement. Life is weird; people are weird. It’s okay to feel weird about that and still have fun.

What’s your five-year plan?

I don’t know that I have a set plan, but I’d like for us to complete another film and have a third in the works by then. I’d also love more than anything to get the opportunity to focus fully on filmmaking while also being able to support my family through my film work.

What’s your favorite film of all time, and what did you learn from it?

I don’t have an all-time favorite, but one of my favorites is Duncan Jones’s Moon. It’s a beautiful and, at times, claustrophobic film: a high-concept sci-fi film that focuses on the small moments. It’s a great character piece on loneliness, and Sam Rockwell does a fantastic job carrying a solo performance.

This is your first feature. How did it come about?

It started out as a ten-page short, kind of inspired by turning 30 and how alienating the monotony of day-to-day life can sometimes feel when you get stuck in an unfulfilling routine. I let Joseph read it and he was really into it, but said it kind of left him curious what happens next. He encouraged me to write a little more, then a little more.

I ended up with forty pages that we decided were way too long to be a short film and that I might as well just keep writing. Six months later, I guess I stumbled my way into the first draft of a 120-page script. We ended up cutting it down to 100 pages by the time I got to my fifth and final draft.

Nothing Really Happens has a great aesthetic. What were your influences?

The influences of my childhood and the era I grew up in (late 80s to early 90s) were a strong visual reference. It has an intentional lo-fi dingy feel to it that I think worked well with it being on a small budget.

Quentin Dupieux’s Wrong was fresh on my mind when I started writing. I love his approach to filmmaking and the idea that something can be thought-provoking without actually needing to say anything – that it’s okay to ask a question and not answer it sometimes, while getting weird along the way. I think it’s actually a lot more fun that way.

The Duplass brothers also have a very grounded and genuine style of filmmaking that I admire. I think there’s probably a little Kaufman, Coen Brothers, and Cronenberg mixed in there too.

Tell us about the casting process.

We have a close group of friends and we’ve all worked together and acted in each other’s projects over the years. I wrote a lot of my characters with the actors already in mind for them, so there really wasn’t much of a casting process.

You managed to pull some impressive performances out of your cast. How did you find this as a first-time filmmaker?

I don’t know that I can fairly take credit for that, as much as I would like to. I have a lot of learning and growing to do as a director in how I communicate my vision to my team, but I think having a close-knit, talented cast and crew that has been working together for years definitely helps.

Having strong, long-time relationships with much of our cast went a long way in helping understand one another’s communication styles – knowing each other’s strengths and limitations, while being honest with yourself about yours.

While none of the characters are based on any of the actors as people, I did try to write in and lean on certain aspects of their personalities and styles of presence for the film. I think being in a familiar environment with people we know and trust helped us get a certain level of comfort on set, and authenticity on screen.

What do you wish you’d known about filmmaking before you dove in?

After finishing the script I told a buddy of mine that we were going to film it during December and have it ready for festivals the next spring. He laughed, but I doubled down with, “Just watch.” Yeah, I was definitely wrong – like, super wrong. Three years wrong. Also, ADs and storyboarding are worth the time and money. Don’t forget that next time, Justin.