‘SMILF’: Why Bridgette is the ultimate antihero of our generation

Ever since the occasionally sweet-natured Tony Soprano (James Gandolfini) made audiences feel divided over whether they should really be rooting for such a cold-blooded monster, male antiheroes have dominated TV. They’re unapologetically cruel, messy without remorse, act with little care for the consequences, and are happy to drag their loved ones down into their black hole with them.

More often than not, anitheroes are also eminently charming and compassionately drawn, so much so that we can’t help but care about them and even side with them in spite of their questionable morals and glaring shortcomings.

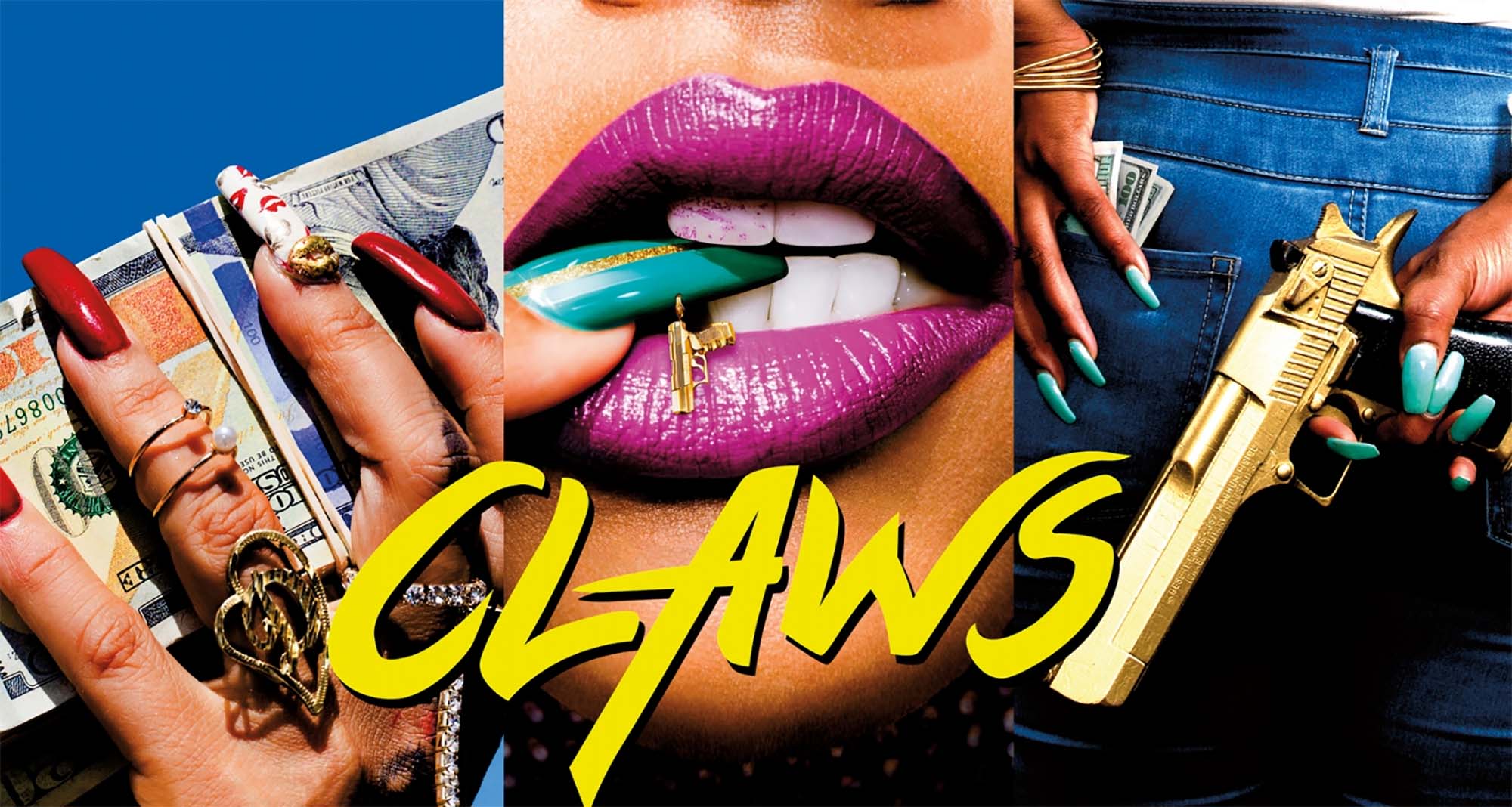

You might have noticed a surge in terrific female antiheroes in the past few years in shows like The Good Wife, Claws, Queen of the South, and UnReal, but by far the best of any recent TV show is Bridgette Bird (Frankie Shaw) from SMILF. In fact, Bridgette might even be the ultimate antihero of our generation of any gender.

However, speaking to Interview Magazine, Shaw (who is the creator and writer of SMILF) argued the character “is not an antihero,” suggesting the application of the term potentially reflects how limiting most portrayals of women in real life and on TV actually are:

Maybe I don’t fit into whatever fantasy idea you have of what a mom should be, but this is just real life and this is my perspective and it’s human . . . (Bridgette) is a three-dimensional character. She’s fully encompassing everything a human is, but to whatever male critic or male viewer or brainwashed woman who is watching, she’s an antihero.

In considering the sort of enigmatic male villains we routinely cheer for when we think of the traditional antihero, Shaw may have a point. After all, Bridgette might not be particularly law abiding, conventional in her ways, or the image of a perfect mother, but she’s not exactly cooking up potentially life-destroying methamphetamines in preposterous quantities or gunning down teenagers who squealed to the cops like most traditional antiheroes do.

Instead, Bridgette is messy, impulsive, and a little self-destructive. However, we’d argue these are exactly the qualities that make her such a great antihero and one like no other we’ve seen before.

Unlike other antiheroes that we’ve seen on TV, Bridgette’s behavior doesn’t pose a threat to innocent people. Sure, she can be a careless mother, but she’s also a loving one doing everything she can to take care of her kid while wrestling with the continued trauma of her own difficult childhood. The only real time we see her participating in any violence towards someone is when she punches a predator in the face after he sexually assaults her.

There are no blurred lines here regarding whether her actions are heroic or villainous – Bridgette is a straight up BAMF and a hero of the highest regard for fighting back. What actually makes the character an antihero is in how she grapples with her dueling impulses and occasionally fails to make the right decisions in taking care of herself. She’s wrestling with the hero and villain of her own emotionality.

Bridgette is deeply flawed and does occasionally unlikeable things, but as Shaw pointed out, that’s also part of being human. In fact, the most unnerving part of Bridgette’s characterization is that her missteps, questionable decisions, and unorthodox sexual desires offer an honest and bold magnification of the struggles many millennials feel.

We may not have all masturbated over a picture of the new lover of our ex, but we’ve definitely stalked them online and felt grubby for it after. Likewise, not all of us may have left our two-year-old home alone to fill up on junk food while we’ve enjoyed a random hookup, but near everyone has likely abandoned their responsibilities at some point in order to satisfy their desires.

What SMILF has ushered forth is a new era of antihero, one that has rewritten the rulebook on what “bad people” and “good people” look like, and that asks the audience to put their own lives under the microscope of heroics to see whether they fare any better. In all likelihood, we may not be as messy or offbeat as Bridgette, but if we’re being brutally honest with ourselves we’re probably just as flawed even if we don’t like to admit it.

As a survivor of repeated sexual assaults and abuse struggling with a binge-eating disorder, Bridgette is growing up as she goes and doing the very best she can. Regardless of our painful histories and struggles – aren’t we all doing the same? To qualify Bridgette as an antihero in the traditional sense is to diminish her achievements as a young woman fighting through the hellscape of her life and coming up smiling.

What the character represents is an antihero for a new generation where the idea of what does and doesn’t count as “heroic” is being rewritten and remolded to better fit narratives full of diverse and unique voices who haven’t been heard from before. The old hero is dead and Bridgette is the future – long may her reign be messy.