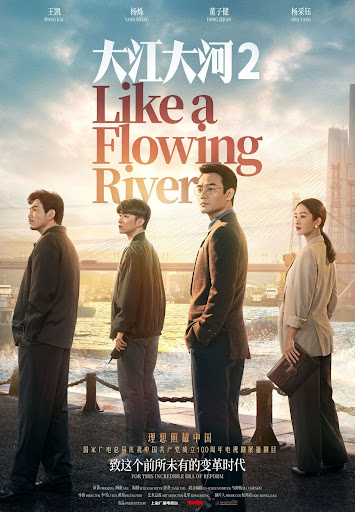

Like A Flowing River 2: A Sprawling Celebration of China’s Open Door Policy.

What’s better than a smash hit? Two smash hits! Despite a second part always being on the table, everything in TV revolves around your viewing figures and nothing is a foregone conclusion. The first series powered to number one in the ratings (on Beijing TV) for each episode and with that, the second series of Like A Flowing River was inevitable.

Based on the novel River of Time by Ah Nai, the sprawling epic (taking place between 1988 and 1982) was conceived as a celebration of China’s open door policy (huge economic reforms across all sectors, handing more power from government to the people). Like A Flowing River focused on the lives of ambitious young Chinese men and women in an era of rapid growth, where rural areas were developing and urbanising and farmers were looking to push themselves into the hustle and bustle of a more modern civilisation. In particular, the show focused on the trials and tribulations of Song Yunhui (Wang Kai), Lei Dongbao (Yang Shuo) and Yang Xun (Dong Zi Jian) ending on a crossroads for each of them. Tragedy, promotions and new horizons.

We begin season 2 approaching 1990. Song Yunhui is working for Donghai chemical, soon to be promoted to a deputy position despite his relatively young age. Meanwhile, Lei Dongbao, still recovering from tragedy (losing his wife in the first season), is given a new opportunity to start a copper wire factory.

Some may find the structure of the series a little frustrating. Around a quarter of the way into this season we are reintroduced to Yang Xun. Then around the halfway point (of the 39-episode run) we’re also reintroduced to Liang Sishen (Yang Caiyu). It’s a show that requires patience given the slow burning nature. When we meet Yang Xun again he’s still full of youthful exuberance. He’s also saddled with debts, overextending himself as he tries to keep his market thriving. Yang has a great will and determination to rise out of the doldrums and capitalise on the expansive economic reforms which saw a boom in private sector enterprises. These reforms brought about by Deng Xiaoping in early 80’s China become a focal point of the intertwining stories. Yang soon sets his sites on opening a hotel.

The characters and their arcs are the major strength of Like a Flowing River 2. Song is ambitious. His family struggled during the shift in government policies, and Song has fought constantly to achieve his rising positions of influence (and more so, to keep them). He pushes forward with the Donghai project, facing bureaucracy and a battle of traditionalism versus evolution. His work ethic also puts pressure on his marriage. His wife, Cheng Faiyan (Zhou Fang), by her own admission is a little lazy and naive. She feels neglected. Cheng is also targeted by her brother and sister-in-law who seek to cash in on Song’s new project. There are financial ramifications which stretch the family drama further, not least Song’s marriage to breaking point.

Lei Dongbao, all hound-dog pathos, is racked with guilt following the death of his wife (Song’s sister). He has a position of responsibility to his workers and local villagers who have invested money and time into him. He can’t face his former in-laws nor Song initially. The former agricultural worker strives to move into industrial enterprise. He forges ahead with the risky copper wire factory despite no guarantees of it being a feasibly profitable project, and he scrapes as much money as possible (not just his own) into getting the project off the ground. Through shortcuts and human errors an explosion in the factory sets the project back and matters are complicated further when irregularities threaten Lei with the attention of the law.

As the show progresses, everything begins to gravitate around the Chemical plant project, which becomes intrinsically reliant on foreign investors and domestic partnerships so vital in these economic reforms but upended at every turn by the conservative elders (mirroring real life). The three old friends, Song, Lei and Yang. intermittently reconverge and soon all have vested interests in Donghai. Liang Sishen returns. She’s the most worldly of the group, having spent time in Wall Street. She represents the most distinct bridge between the burgeoning China and the international market full of expansive opportunities, but she herself is saddled by the weight of expectation and belittlement from her conservative and traditionalist grandfather. He built a prosperous empire in pre-reform days and often reminds her. The constant reneging and ever-changing government restrictions prove a thorn for all of the principal characters as conflicting ideologies of communism and socialism naturally slow business progress.

The open door era is perhaps the most fascinating of modern Chinese history. A post-Mao generation pushing back against the current regime, searching for more freedom of enterprise and expression. Yet still, a friction between evolution and conservatism would occasionally cause difficulties for individuals, companies and industries, personified in Chinese history by Deng Xiaoping and Chen Yun, two key figures in the reforms, who had differing beliefs in how to implement reforms (with Yun having the more conservative approach). Our young protagonists, pitted against significant change, must also contend with these conflicting values still upheld by the older generation. If Song and Liang approach problems with poise and refrain, then Yang and Lei charge at issues like a bull.

China would inevitably expand and open (even just small) doors to foreign investment and trade. One key obstacle facing the Donghai project is the use of foreign machinery. The intricacy of these deals due to ever fluctuating international relations makes it difficult, whilst Song’s preference for American products is blocked at every turn by his conservative superiors who want to use cheaper, inferior Japanese machinery for the sake of maintaining established relationships over building newer ones.

Director Li Xiu never shies away from shining a light on the difficulties faced by companies, and the people within them, during this time of major economic reform. Old versus new, tradition versus progress, insulation versus expansion. The aspirational rural villagers, seeking to broaden their world to the big City lights have mounted themselves with debts from local strong arms, banks and relatives. China continues to develop, but 30 years ago that boom was particularly huge and it goes without saying, many probably pushed their ambitions to absolute financial limits. Success or ruination on a knife edge.

Like a Flower River 2 is an enthralling show that will interest lovers of history as much as drama. From a technical standpoint the show is lavish. The production design is very impressive, beautifully creating a period of time that looks sprawling, rather than confined to basic interiors. It has impressive production values, with stunning cinematography. The music by Dong Yingda is the perfect balance of uplift and melancholy. The show never succumbs to melodrama either, which can sometimes hamper the international appeal of Chinese dramas. Wang Kai and Yang Shuo in particular are superb, headlining an excellent cast.

Author: Tom Jolliffe